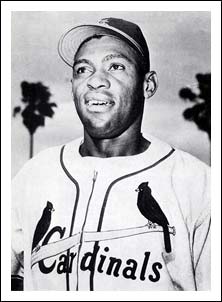

Thomas Edison Alston

First Baseman, 6'5", 210 lbs. Bats : Left Throws: Right

Born: January 31, 1926, Greensboro, NC

Died: December 30, 1993, Winston-Salem, NC

Alston was one of three Western Canada players who went on to become the first blacks to integrate major league teams – Alston with the St. Louis Cardinals, John Kennedy Philadelphia Phillies and Pumpsie Green, Boston Red Sox.

After high school and a stint in the Navy, the tall first baseman began his career in the Negro Leagues with the Goshen / Greensboro (NC) Red Wings and later suited up with the Jacksonville Eagles, a touring club which was hired in 1950 to play in Canada as the Indian Head Rockets.

After two seasons with the Rockets (1950-1951) Alston kicked off his career in organized baseball way down in the Southwest International League. In that initial season of pro ball, Alston must have thought he'd never left Canada -- at least eight of his teammates with Porterville had played on the prairies (including Jesse Blackman/Blackmon, Walt Tyler, Chet Brewer and Les Witherspoon). After a superb rookie campaign (.353-12-59) Alston quickly made his way up to the San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League.

With a jump to the PCL, he even improved almost all of his batting marks with 23 homers and 101 runs batted in. That opened some eyes and the Padres sold his contract to the St. Louis Cardinals.

"Lefty O'Doul, the San Diego baseball manager, claims that Tom Alston, former Indian Head first-baseman, will rattle the ball off big league fences before long ... Alston had 14 homers in seven weeks with the San Diego club in the Pacific Coast League ... O'Doul says 'He's one of the greatest prospects I've ever seen. Here's a kid who wants to learn and is willing to listen and work like a beaver to get places. I don't see how he can really miss developing into a great hitter.' ... Alston, a 22-year-old left handed batter, is making San Diego fans forget the exploits of Luke Easter, Harry Simpson and Orestos Minoso. ... O'Doul is one of the greatest managers in the game and gave Joe DiMaggio his start." (Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, June 5, 1953)

On April 13, 1954 he became the first black to suit up with the St. Louis Cardinals (two others who played in Western Canada figured in the Cardinals' plans to integrate - Len Tucker had been the first black signed by the Cards and Eloyd Robinson the third).

While performing well at the Triple-A level, Alston never lived up to the high promise in the majors. There was a major reason.

After ending his playing career and returning to Greensboro, he spent most of the next decade in mental hospitals. Alston had begun hearing voices during his playing days and on at least one occasion attempted suicide. In 1959 he burned down the church near his old ball field in Greensboro. When released from one institution, in 1967, he set fire to his apartment and was sent to another hospital. With both medical and mental problems, Alston survived on disability benefits until his death in 1993 at age 67.

BA HR RBI

1950 Indian Head IND N/A

1951 Indian Head WCBL N/A

1952 Porterville Southwest .353 12 69

San Diego PCL .244 2 26

1953 San Diego PCL .297 23 101

1954 St. Louis NL .246 4 34

Rochester IL .297 7 42

1955 Omaha AA .274 6 59

St. Louis NL .125 0 0

1956 Omaha AA .306 21 80

St. Louis NL .000 0 0

1957 St. Louis NL .294 0 2

The following story about Alston’s tortured life appeared in the April 10, 1991 editions of the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. It was written by columnist Scott Pitoniak and was selected for inclusion in The Best American Sportswriting Anthology 1992.

Thomas Edison Alston no longer hears the voices. Hasn’t for 30 years. But he remembers them. Clear as a bell. The mere thought of them still causes anxiety, still prompts him to break out in a nervous sweat. The former Rochester Red Wings first baseman vividly recalls that autumn evening in 1957 when he tried to fall asleep, but couldn’t because the words wouldn’t go away.

”Nobody was around, but this voice kept telling me, ‘It’s time to meet your maker. It’s time to meet your maker,’” Alston recalled from his Greensboro, N.C., apartment. “The voice was so powerful that I got up out of bed, grabbed a razor and hopped in my car. I was going to do what the voice had told me.”

Alston remembers driving to a backroad on the outskirts of Greensboro, and getting out of his car. He dragged the razor across one of his wrists, but made only a small cut. Blood trickled out. Before he could try again, a sheriff’s car pulled up.

”What you doing, son?” the officer asked Alston.

”Nothing sir,” he replied.

”Well, you best be getting out of here,” the sheriff said.

Alston got in his car and drove home.

His suicide attempt had failed, but his problems were far from over.

During the ensuing years, the man with the sweet swing but troubled soul would see his promise as a professional baseball player go unfulfilled. In the spring of 1959, the first black player in Red Wings and St. Louis Cardinals history returned to Greensboro, distraught and broke. Two days after setting foot in his hometown, he went to a church in the middle of the night, poured kerosene on the pews and lit a match. The building burned to the ground. The police took Alston away.

He spent parts of the next 10 years in two different mental institutions in North Carolina. He was released in 1969, and has been living by himself in a two-bedroom apartment in the eastern part of Greensboro. He’s still on medication, still collecting disability benefits, still trying to make ends meet.

Occasionally, a letter from some fan seeking an autograph arrives in the mail. Occasionally, someone at the grocery store down the street recognizes him as a former major leaguer.

”That makes me feel good,” said the 65-year-old Alston. “Reeaalll good.”

Great expectations

According to The Baseball Encyclopedia, Thomas Edison Alston spent parts of four seasons in the major leagues. He appeared in 91 games, hit four home runs and batted .244. Mediocre numbers. Numbers of unrealized potential.

So much more had been expected of him when he arrived at the Cardinals training camp during the spring of ‘54.

”There was a feeling among some that the guy might be a fixture at first base for several years,” recalled Bob Broeg, longtime baseball writer and columnist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “He looked like a real good athlete. He was outstanding defensively. I remember one foul ball, in particular, when he raced down the right-field line and made this spectacular catch. Snatched the ball right out of the bullpen.”

Two things immediately caught people’s attention about Alston: his size (he was 6-feet-5, 200 pounds) and the color of his skin (he was the only black player in camp).

The Cardinals had long been criticized for their refusal to integrate, but when famous beer baron August Busch bought the team in the early 1950s, he set about to change that policy. He instructed his scouts to start looking at black prospects, and in January 1954 he purchased Alston’s contract from the San Diego Padres, then an independent Triple-A team. The Cardinals paid San Diego $100,000 — pocket change by today’s standards, but headline-grabbing money back then.

Busch made a big production of the signing of Alston, who starred at North Carolina A&T before receiving a degree in physical education in 1951. The Cardinals owner rented a Hollywood, Calif., suite for the press conference and served caviar and Budweiser.

”The only black guys in the place,” Alston recalled, “were me and the valet.”

Alston was coming off an outstanding season in which he batted .297 with 207 hits, 23 homers and 101 RBI. But despite the scintillating numbers, he didn’t feel right. For more than a year, his throwing arm had been weak. He was constantly tired. And there were the voices. He began hearing them while playing winter ball in Mexico in 1953, though he never told anyone about them.

Add to this the burden of being black in a game that had been integrated only seven years earlier when Jackie Robinson signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

”When we played exhibition games down south, the Negro players had to stay in shabby hotels while their white teammates stayed in the good hotels,” Alston said. “Segregation was an accepted way of life back then. The Cardinals had the rap of being bigoted. I didn’t experience anything real bad. None of the players were friendly to me, but they weren’t rude.”

Despite the obstacles, he performed well enough in spring training to convince the Cardinals to make him their starting first baseman.

”I thought I had a fair spring, but I think they were giving me a chance because I was Mr. Busch’s pet project,” Alston said.

Headed to Rochester

In the third game of the ‘54 season, the Chicago Cubs pounded St. Louis, 23-13, at Wrigley Field, but Alston smacked a home run. It was his first big-league hit.

The following day, he came off the bench to pinch hit for Steve Bilko and drove the first pitch over the wall for a three-run homer that lifted the Cards to their first victory of the season.

Alston appeared to be on his way. He was. To the minors, not stardom. After his auspicious start, he struggled at the plate and on June 30 was demoted to Rochester, the Cardinals’ Triple-A affiliate.

”I enjoyed my stay there,” Alston said. “The guys were friendlier than the Cardinals were. I lived with a black couple. I don’t remember their names. I think the guy was a postal worker. I pretty much kept to myself. I was no carouser. Nightclubs and drinking, that just wasn’t me.”

Harry “The Hat” Walker was the Red Wings manager at the time. He remembers Alston “as a quiet guy. Real cooperative. Did what you asked him to.” Lou Ortiz, a second baseman for the ‘54 Wings, said Alston “like all the colored players at that time, had it tougher than the rest of us, but I can’t remember him ever losing his cool about anything.”

Alston doesn’t recall being subjected to any racial hatred while playing for Rochester, but Walker remembers one incident when an opposing player peppered him and Alston with epithets.

”I told the guy to shut up, and he said, ‘You wanna make something of it?’ and next thing you know he and I are wrestling like two alligators in the dugout,” Walker said. “My neck still hurts from crashing down those dugout steps.”

Alston rediscovered his stroke during his stay in Rochester, batting .297 in 79 games with seven homers and 42 RBI. St. Louis recalled him in September and he spent the rest of the season in a reserve role.

During the next three summers, he yo-yoed between the majors and the minors.

”I really believe he was putting too much pressure on himself because he wanted to do well, being the first black Cardinal and all,” said Bing Devine, the former Rochester and St. Louis general manager.

”Sure, there was some external pressure, but I really believe some of his problems were simply a case of him trying way too hard.”

Mood swings

Alston’s inability to perform the way he had when he was healthy led to depression, which contributed to his suicide attempt in 1957. Although he never told the Cardinals about that incident or the voices inside his head, longtime trainer Bob Bauman suspected something was wrong.

”He would have these mood swings,” recalled Bauman. “He began losing a lot of weight. I diagnosed him as having neurasthenia (a condition marked by nervous exhaustion). We had a psychiatrist take a look at him and he diagnosed the same thing.”

Alston said the psychiatrist didn’t ask him any questions. “It was the damnedest thing,” he said. “The doctor didn’t say a word to me. Just came in and gave me electro-shock treatment.”

In the spring of 1959, Busch met with Bauman and asked him what they could do to help Alston. Bauman and the psychiatrist suggested that Alston go to a mental institution to receive treatment.

”We felt we could help his problem with diet, medication and regular sessions with a psychiatrist,” he said. “I was really afraid that he was going to do something to hurt others or himself if we didn’t do something. But he refused to go to the mental hospital, and we couldn’t force him to.”

Instead, Alston returned to Greensboro, and torched the church next to the field where he grew up playing sandlot baseball.

”I don’t know why I did it,” he said. But in a 1982 interview he told the Greensboro News & Record that he committed arson because he felt his community needed a new chapel.

He spent all but two months of the next eight years at Cherry Hospital, a state mental institution in Goldsboro, N.C. He was released in 1967, but two months later he set his apartment on fire and was sent to John Umstead Hospital in Butler, N.C.

He was released in 1969.

Alston said his problems — mental and physical (he has severe arthritis and high blood pressure) — have prevented him from getting a job, so he scrapes by on disability and Social Security.

He has written former ballplayers asking for financial help, but said few have answered his letters.

”Willie Mays sent me an autographed picture, but that’s about it,” he said.

Several years ago, the children on his block organized a baseball team and asked him to be their coach.

”I wanted to,” he said, “but I just wasn’t up to it.”

Last summer, he flew to St. Louis to be part of a baseball card show along with former Cardinal greats Stan Musial and Lou Brock. The promoters billed him as “the legendary Tom Alston, the Cardinals first black player.”

”He got along with the fans well, but I doubt we’d have him back,” said St. Louis card dealer Rick Hawksley. “Nothing against Tom, but I just don’t think that many people remember him.”

Alston spends much of his time reading the paper and watching sports on television. A couple of times a year, he journeys to War Memorial Stadium, home of Greensboro’s Class A team, to catch a game in person.

”It used to be that people there would remember me, and yell things like, ‘Hey, there’s Mr. St. Louis Cardinal,’ but it doesn’t happen much any more,” he said. “Guess I’m getting old.”

He said he is disappointed, but not crushed that his big-league career didn’t pan out the way he wanted it to. He’s happy he at least made it as far as he did, and figures if he hadn’t gotten sick, he might have had a more productive career.

”I know I was a good baseball player,” said Alston, who was inducted into the North Carolina A&T Sports Hall of Fame in 1972. “Until I started having those problems with my left arm, I hit line drives all over the place. Crisp line drives.”

The crack of the bat remains a pleasant sound to him.

Much more pleasant than the sounds of voices from a troubled past.