Steve Enloe Wylie

Batted Right, Threw Right

6' 1", 180 lbs.

Born : May 7, 1911, Clarskville, Tenn.

Died : October 23, 1993, Clarksville, Tenn.

Wylie began his baseball career as a teenager pitching for the semi-pro Clarksville Stars from 1927 to 1930.

Later, he played for the Crofton Browns, a team owned by a Crofton, KY coal mine company. Players would suit up for baseball in the summer and work in the mines in the off season. It's believed it was while Wylie was with Crofton that he was scouted by Negro League clubs.

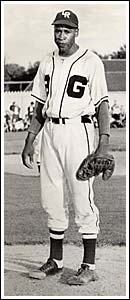

Then 33, the big righthander, began his Negro League career in 1944 with the Memphis Red Sox. Soon he would be in the uniform of the fabled Kansas City Monarchs and a teammate of the fabulous Satchel Paige and an infielder by the name of Jackie Robinson, who would integrate major league baseball in 1947.

In fulfilling the expectations of Monarchs’ manager Frank Duncan, he used a blazing fastball and a sharp-breaking curve to fashion a 7-3 record in 1946 as the Monarchs won the Negro American League pennant before losing to the Negro National League’s Newark Eagles in the World Series. (Riley, James A. The Biographical Encyclopedia of The Negro Baseball Leagues. Carroll & Graf, 1994, p 885-886)

Wylie pitched for the Monarchs until 1947 when the Negro Leagues began to collapse as Negro Leaguers began to follow Robinson to major league ball.

In the summer of 1948, Wylie began the season as a key member of the barnstorming George Ligon’s Colored All-Stars. He had been a teammate of George’s brother, Rufus Ligon, in 1944 in Memphis. The Ligon's were a familiar sight on the prairies in the late 40s and early 50s.

As a Monarch, Wylie had earned $400 a month. "A lot of the guys got more. Now, Satchel, he got 10-percent right off the gate. He was the biggest draw they had," said Wylie. "When I went to Canada, I was making $700 a month." (Clarksville Leaf-Chronicle, June 10, 1990)

Near the end of June 1948, Wylie pitched the All-Stars to top money in the Brandon, Manitoba invitational tournament downing the host Brandon Greys 5-3. It wasn’t long after that he would be in the uniform of the Brandon club and became recognized as one of the great “money players” on the tournament trail in Western Canada.

In July, Wylie tossed a two-hitter and struck out twelve as Brandon whipped the Muskogee Cardinals 11-1 for first prize money in the $1,000 Brandon tournament.

A few weeks later, Wylie was the hero as Brandon began play in huge Indian Head tournament with a 1-0, 11-inning victory over Lake Valley. Wylie pitched a two-hitter and won his own game belting a double and scoring in the bottom of the 11th. Wylie pitched a three-hitter in the final as Brandon took top money with a 4-3 win over Sceptre before a record crowd of 16-thousand fans.

In mid-August, the Tennessee-native allowed just three hits and fanned thirteen to lead Brandon to a 5-3 win in the opening game of the Manitoba Senior Baseball League final. A week later Wylie scattered eight hits and struck out twelve in pitching Brandon to the league championship. He finished the season with a record of 12-1.

"Five imported Negro stars, Koney Williams, Bus Quinn, Thad Christopher, Raphael Cabrera and Steve Wylie proved a sound investment for the backers of the Greys as they turned a "good" club into a "dream team". (Brandon Sun, December 30, 1948)

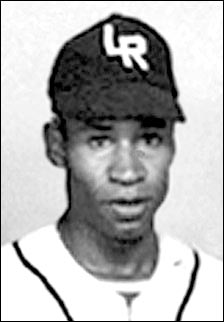

The winning ways continued in 1949. Back at the Brandon tournament, this time in the employ of the Minot Merchants, Wylie tossed a two-hit shutout as Minot beat Transcona 6-0 to advance to the final.

In July, Wylie pitched two shutouts, a one-hitter and a four-hitter, to lead Minot Merchants to the $1,000 top prize in the Indian Head Tournament. Wylie, who pitched Brandon to the title in 1948, beat Moose Jaw 1-0 in the quarterfinals, then shutdown Wilcox-Weyburn 3-0 in the championship game before a crowd of 12-thousand.

At Minot, August 7th, Wylie received a gold watch as fans held a Steve Wylie Day. He promptly pitched a four-hitter as Minot beat Brandon 3-2.

He began the 1950 season pitching in Fulda, Minnesota then answered a call from the Minot Mllards and drove 500 miles to team up with Satchel Paige. Paige had agree to pitch three games with the North Dakota club, but just three inning stints. Wylie was the backup.

He left Minot, however, to join the Swift Current, Saskatchewan Indians and was back trying to win the Indian Head tournament for the third straight season. He won his preliminary match but Swift Current was upset in the semi-finals.

Wylie joined the North Battleford Beavers of the Western Canada League for the 1951 season. Not surprisingly, a tournament victory was among his first games of the season. He pitched a six-hitter to lead the Beavers to an 11-1 win in the final and top prize money of $2,000. Wylie also pitched for the Beavers in 1952 before moving on to the Grandview Maroons, of the Manitoba-Saskatchewan League, in 1953.

In 1952, Wylie pitched a masterpiece, striking out 23 in front of a scout for the Chicago Cubs. He still has a picture of the man who scouted, but did not sign him. "I'd done got up in age and I didn't make it. That's the guy that scouted me. I forget his name," said Wiley. "I struck out 23 and he still said I wasn't a pitcher." (Clarksville Leaf-Chronicle, June 10, 1990)

Wylie also reported playing for clubs in Toledo, Ohio, Fulda, Minnesota and Sioux City, Iowa. He finished up his career in 1956 pitching in Ontario's Intercounty League with the Galt entry.

"I never could throw the screwball," said Steven Enloe Wylie. "I had a knuckleball, a curveball, a slider and a fastball." "I could throw from three angles. I would throw it overhand, from three-quarters and sidearm." (Clarksville Leaf-Chronicle, June 10, 1990)

On June 12, 1990 the City of Clarksville honoured Wylie with an official proclamation recognizing the achievements of Negro baseball and specifically Steve Wylie, hometown hero.

"I played in a lot of different places," said Wylie. "I won a lot of them, and I lost a lot of them." (Clarksville Leaf-Chronicle, June 10, 1990)

Wylie died at Clarksville, October 23rd, 1993 at age 82.

From : It's A Black Thing, published by Kids in Control, Clarksville, TN.

The following publication -- part of an oral history series by students in Clarksville -- provided by Eleanor Williams, Historian, Montgomery County, Clarksville, Tennessee.

"THE EYE OF AN ERA!"

An Oral History solicited from STEVE ENLOE WYLIE

Professional Baseball Player

BORN: May 7, 1911 (Black Male)

BIRTH PLACE: North 2nd Street, Clarksville

FATHER: Charlie Wylie

MOTHER: Diane (Moore) Wylie

WIFE: Anna Love (Elliott) Wylie

Steve states that at the time of his birth he was living on top of the hill behind the now present Shoney's restaurant stand, he says that there used to be an old fort there.

His father, who was born right at the end of slavery, worked on the railroad and in the mills of Montgomery County and Evansville, Indiana.

Steve recalls that in the 1920's his grandparents, who were ex-slaves, lived in what was known as a "shot-gun" house. It had a bedroom, kitchen and 2 rooms upstairs for the kids to sleep in.

Steve is the last remaining member of his family, he had three sisters and two brothers all older than him, but they have all passed on.

As a child he went to Burt School, an all colored school during segregated times, on Franklin Street. There he completed both grade school and high school. This remarkable man still remembers many of his teachers including : Mrs. Bessie Cross, Mrs. Margie Stamps, Mrs. Clara McReynolds, and Mrs. Hattie Barksdale all grade school teachers and Mr. Robert Trice, Mrs. McKinney, Mrs. Collins, Mrs. Sims, Mr. Blackburn, Mr. Allison all high school teachers. He was graduated in the class of 1933.

He says that when he was a child, black people went to high school sporting events for entertainment, or sometimes they went to a dance hall for colored called Buck's Hall on 6th Street.

Also, the City of Clarksville had a black baseball team that would play other teams from Louisville, Indianapolis, and Milwaukee, and this was a very big event to go to after church on Sunday.

Steve says that Clarksville was not as bad as other places in the South, because the local blacks would fight back even though they would be put in jail. Judge Cunningham was also more lenient than other judges. Still when blacks fought back they would always end up on the wrong end, but they refused to cower down.

Steve's grandfather used to tell Steve that if he had his way, he'd put all whites in jail.

Steve reflected that black ministers in times past, were not as fast and after money as they are now.

Steve stated that when he was a child, Clarksville was just a farm town, and that all of his ancestors originally came from places in Montgomery County like "Round Pond", "Hematite", and "Blaton".

When he was a young man, the only government work that blacks were allowed to do in Clarksville was street cleaning or driving mule teams. Later they were allowed to concrete curbs and gutters.

He recalls that black grocery stores in Clarksville included: Jessie Darden's on Cedar Street, Albert Roberts on Dodd Street, Les Thomason on Poston Street, a store operated by Thomason's nephew in Lincoln Homes, Warfield Grocery on Ford Street, and Landers Grocery on Ninth Street, Additionally, Pope Garrett operated a dry cleaners.

Steve also recalls some black "fortune tellers": Mary Blakley, who was blind, and lived on Eleventh Street, Mrs. Fry also residing on Eleventh Street Jenny Daniels -Franklin Street

When asked about (Black Bottom), Steve advised that it was a rough place and that he never did go there,

Steve says that in 1923 or 1926 when Indian Mound was all Cherokee Indians the Negro's started intermarrying with them and the whites couldn't tell the Indian children from the Negro children. So to keep the blacks from going to the white schools like the Indians did, the whites burned down the schools in Indian Mount and in 1926 a lot of blacks left Indian Mound and settled in Woodlawn and Clarksville.

He remembers that a lot of black men worked at the mill and the snuff factory, but most of them were farmers or railroad workers. Still he says that quite a few of the blacks drove trucks and wagon teams for Brollin & Harris and Richardson & Pettus stores delivering coal and stuff to stores and homes.

In 1930 only nine to eleven thousand people lived in Montgomery County and Franklin Street (because of bootlegging) was the roughest part of Clarksville.

He says that Chief of Police Roberson was a good fellow but that all of the police would collect money from the gamblers and guys who sold whiskey. Whiskey then was 25 cents a half pint and $2.50 a gallon and according to how much you sold, would be how much you paid the police.

He personally witnessed that a particular Pool room which had sold six or seven gallons of whiskey on a Friday or Saturday night, had to give the police their cut, when they showed up to collect on Monday morning.

Steve started playing baseball in 1923 for the Clarksville colored team as a pitcher, they played against Hopkinsville, Bowling Green, then when times got bad he went to Crofton, KY, and Ft. Wayne, Indiana where he worked.

There he was scouted and picked to play for the Kansas City Monarch's colored baseball club. While there he became a relief pitcher for Satchel Page and later Jackie Robinson joined the team.

He recalls that one time he drove 500 miles from Minnesota to Minor North Dakota to relieve Satchel Page in 1946, Page only pitched three innings.

He says there were times that they would draw a bigger crowd than even the New York Yankees when Satchel would pitch and that Satchel would receive as much as two and three thousand dollars a game.

He also played with Josh Gibson, a man he praises as the greatest baseball catcher there ever was.

Steve says that there were 50 Negro baseball pro teams, and that he himself pitched four no hitters in his life.

He says that when he played for the Kansas City Monarch's, they came to play Nashville two or three times a year.

When baseball became integrated in 1947, he let the Kansas City Monarchs and so did Jackie Robinson.

Steve says he left because the team was sold to Tom Barrett from Dale Williams and that Mr. Barrett got rid of all the older players and kept the younger ones. Mr. Barrett felt he could make more money by sending them to the big leagues.

So Steve went to Canada and played ball from 1947 to 1956. He played for the North Battleford Beavers and the Winnipeg Bucs of Sasquatchan. Then he played for the Gualt All Stars out of Galt, Ontario. He also played with teams from Iowa and Minnesota.

Once he had been scouted to play for the Chicago Cubs but Horace Lisenbee (a famous white ball player from Clarksville) had him turned down by saying that Steve could not pitch well enough.

Steve began playing black professional baseball in 1934 and in 1956 he played his last game in Gualt Ontario close to Detroit.

Recently in June of 1989, the Atlanta Braves Baseball Club and the Southern Bell decided to honor these forgotten black baseball greats. Steve was brought there for three days, where he was presented with a commemorative baseball bat, a $300 watch, and they tried to pay him past wages to equal the pay he should have received justly when playing ball.

Steve was invited to attend the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooper Town but could not afford the funds it will take. This was to be on June 12-13 of 1990.

Steve says that in the 1930's he went into the Navy and the blacks could only be mess attendants, cooks or stewards, and it took a black man 18 months to attain his first rate of $36.00 a month. While his white counterpart received his first rate automatically after his 3 months of training.

In fact he says if a blackman did not have a white officer who would give him a break you could be there 20 years without receiving a rating and you were always referred to as Nigger or Shine.

Steve says you were given a ratings test every year, but you could not see the results and you always failed so you didn't get rated.

Steve says there were no black Navy officers or sergeants then, but he does recall seeing Army black officers and sergeants, but they were always stationed overseas in Guam, Honolulu, or China.

Other Recollections of Steve Wylie:

Steve says that in someways prejudice is worse in Clarksville today than it was yesterday in the 1920's. Because then you could only be what the white man let you be. You didn't have jobs like clerk, opened up to you, so you never looked forward to it because you knew you'd never get the job.

He remembers that the black voters helped to get the Trane Company here. But when they got here they would only hire blacks as janitors until the 60's.

Steve later worked as a welder in Trane Company for nine years.

Steve recalls a black man named Mr. Dickson in the 1940's who was executed by the state for the crime of rape of a white woman. Steve says everyone used to see this man riding the bus to Round Pond where would go meet this white woman. Steve says it was common knowledge that this woman had already given birth to two children fathered by Mr. Dickson. But somehow he was charged with rape and executed.

Steve recalls with fondness the famous Dr. Burt, Steve went to school with Dr. Burt's daughter and with his own later to be wife Anna Elliott.

Steve used to swim in a swimming pool behind Dr. Burt's infirmary, and Dr. Burt once operated on his foot.

The first black police officers that Steve remembers in Clarksville is Henrey Newell, Elias Pettus, and Otis Martin in the late 1950's he says they were Auxiliary Policemen and not allowed to arrest white people.

Steve says he has two daughters and so many grandchildren and great-grand- children, that he would have to throw a rock on top of the house to see how many ran out so he could count them all.

All previous information on Steve Enloe Wylie was obtained by the author, Ronn Evans, in an interview at his home on June 05, 1990. I found this man Mr. Steve Enloe Wylie to be a man of unreproachable demeanor and a past that demands the respect he is due. Not only was he a pioneer in the field of black baseball, but truly the Eye of the Era of Baseball integration.