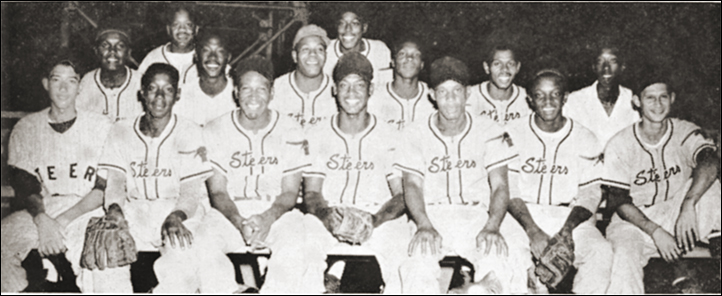

The 1956 Texas Jasper Steers - Back (L-R) Elmer Simmons Sponsor, Goose Goff 1B, John Jones C, John Johnson P, O.B. Robison P, Otha Richardson CF, Ellis Triggs CF, Davis B. Standfield Bus Mgr

Middle - John Wingate 3B, Henry Francis 3B, Raymond Lacy C, Vernon Hicks LF, Charles Nichols MGR

Front - Ed "Cut" Brown 2B, Sonny Boy Hampton SS, Robert Knight 3B, Thomas Snoddy 1B, Frank Picken P

1957 Texas Jasper Steers finished in a tie for 4th place in the National Baseball Congress Tournament at Wichita. On the roster : Robert Knight, Cut Brown, Andy Valenzuela, Roy Williams, James McGee, Frank Pickens, John Jones, John Wingate, O.B. Robison, Willie Smith, Charles Nichols, Pete Dickson, Caddy Nelms, Elan Walker, John Johnson, Robert Colligan.

Jasper, in 1954, was a city of about 4,500 people. In the extreme east of the state, it was much closer to the Louisiana border (just 40 miles away) than any major city in Texas.

For a team which made only a brief visit to the prairies seventy years ago, the Texas Jasper Steers made quite an impression. The team appeared to spend less than two weeks in Canada, played in one tournament (losing their only game, a 1-0 heart-breaker). Published sources indicated the Steers played just six games in the country.,

Jasper Steers Background.

Jasper & C.C. Risenhoover

The impact was in the number of players from the Steers who suited up in Saskatchewan. At least six, maybe seven, were known to have played in Canada - Charlie Nichols (Estevan 1950), O. B. Robison (Baton Rouge,Winnipeg Buffaloes, Moose Jaw 1952), Tom Snoddy (Ligon's 1950), Roy Williams (Regina 1953), John Wingate (Estevan 1950), Frank Pickens (Saskatoon 1952, Regina 1953) and perhaps John Jones (Indian Head 1952).

Newspaper reports showed the Steers (who had already been busy with exhibiitions in Louisiana and Oklahoma among other spots) on the way up to Canada in the first week of July, heading for the big tournament in Indian Head, near Regina, July 14th.

Newspaper reports showed the Steers (who had already been busy with exhibiitions in Louisiana and Oklahoma among other spots) on the way up to Canada in the first week of July, heading for the big tournament in Indian Head, near Regina, July 14th.

On July 7th, the Telegraph-Bulletin of North Platte, Nebraska (where the Steers were to play that night) noted the Steers had a record of 38 wins, two losses and one tie on their barnstorming tour to Canada. It was claimed the team had a string of 30 straight victories powered by an outstanding one-two punch on the mound. Right-hander O.B. Robison was said to have 17 consecutive wins while lefty Alvin Jackson (right), a 17-year-old high schooler (who would later pitch in the majors with the Mets and Pirates), showed a record of 15-0.

On July 7th, the Telegraph-Bulletin of North Platte, Nebraska (where the Steers were to play that night) noted the Steers had a record of 38 wins, two losses and one tie on their barnstorming tour to Canada. It was claimed the team had a string of 30 straight victories powered by an outstanding one-two punch on the mound. Right-hander O.B. Robison was said to have 17 consecutive wins while lefty Alvin Jackson (right), a 17-year-old high schooler (who would later pitch in the majors with the Mets and Pirates), showed a record of 15-0.

While the math didn't add up, the story went on to say pitcher Chico Martinez was 8-0 and "Candy" Keegans (the named used by C.C. Risenhoover) 5-0. Those numbers would have given the Texas nine at least 45 wins.

When Jackson signed a pro contract with Pittsburgh in 1955, a newspaper story said he had compiled a 23-3 mark on the 1954 tour.

Among the teams the Steers faced along the way were the Florida Cubans and the Jacksonville, Florida, Eagles, teams familiar to baseball fans on the prairies.

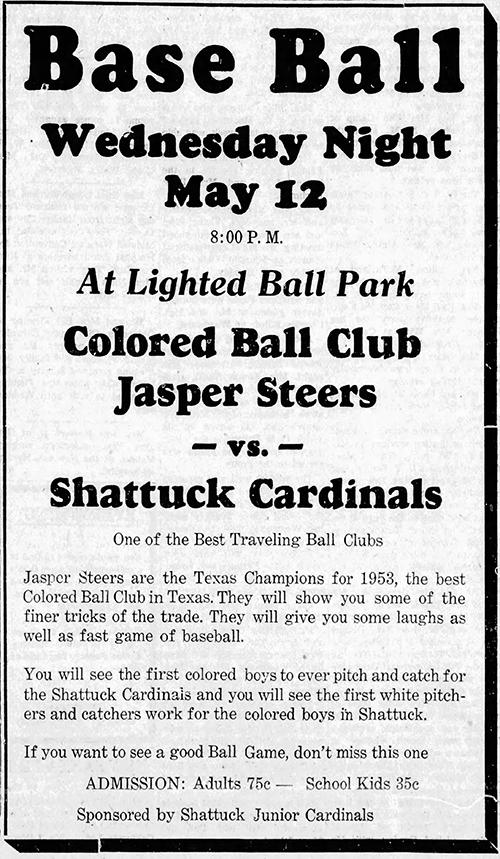

The Steers had captured the 1953 Texas Negro Championship and, after taking 1954 for the trip to Saskatchewan, repeated as Texas champs in 1955. In 1956 the team was crowned the champions of the National Baseball Congress All-Dixie Negro Championship and finished tied for 11th place in the annual NBC Tournament. They repeated as Dixie champs in 1957 and tied for fourth place in the NBC Semi-Pro Championship.

The 1954 Canadian leg showed :

(July 14) Indian Head Tournament. Southpaw Alvin Jackson lost a heartbreaker as the Steers were knocked out of the tournament losing to the Saskatoon Gems 1-0. The only run came in the fourth inning as Percy Trimont was hit by a pitch, sent to second on a sacrifice and scored on Bev Bentley's single. Bentley had two of Saskatoon's five hits. Bobby Doig fired a three-hitter for the shutout. He fanned nine and retired the last 17 in order. Jackson yielded just five hits.

Jackson and

Powdrill

Doig and Bennett

(July 17) Steers scheduled to play at Assiniboia.

(July 20) The touring Texas Jasper Steers, filling in at the last moment for the Saskatchewan League's Indian Head Rockets in an exhibition encounter in Regina, easily defeated a select team of players from the Southern League's Regina Royal Caps and Red Sox 8 - 1. The hosts found the southpaw slants of the Steers' hurler Alvin Jackson a trifle mystifying as he set the Reginans down on three meagre hits while fanning 13. Jackson didn't yield a safe blow until the 6th frame when Bunny Smith beat out an infield roller. The first solid blow off Jackson came in the 8th when Tommy Leverick tripled after two were out. Smith followed up with a sharp single to plate Leverick with the sole tally for the Queen City Combines. While the Reginans were frustrated at the plate, the Steers rapped out 12 safeties off the offerings of two chuckers, loser Lloyd Woolley and Leverick. Roy Williams, who performed with the Regina Caps of the Saskatchewan League last summer, led the way with a bases-empty homer in the 5th and a triple in the 7th. Ray Lacey also enjoyed a fine outing with a double and two singles in five trips. Charlie Nichols was next in line with a double and single in five attempts, driving in three runs. Jackson and shortstop John Henry Jones accounted for the other extra-base blows, both lacing two-baggers. Jackson (W) and Williams

L. Woolley (L), Leverick (6) and McNabb, Manz (7)

(July 21) A scheduled double-header between the Gems and Rockets at Regina turned into a farce as Indian Head was unable to field a team and filled in with replacements from the touring Texas Jasper Steers. The first game was called after 4 1/2 innings with the Rockets ahead 14-4, then rain washed out the second contest with Saskatoon leading 2-0 in the second inning. Gem manager Ralph Mabee lodged a protest (which was upheld). Saskatoon had infielder Cliff Pemberton and outfielders Percy Trimont and Mario Herrera on the mound. Orlando Arango set the Gems down on five hits. Roy Williams of the Steers, who had played in 1953 with the Regina Caps, had 2 singles and 4 RBI's as a replacement player for the Rockets. Catcher Miguel Miranda had three walks in three trips and scored three times.

Pemberton (L), Trimont (3), Herrera (4) and Bennett

Arango (W) and Miranda

(Late July) Risenhoover " ... One other recollection of his summer is pitching a 17-inning game in Canada before losing 1 - 0."

One of the features which caught our eye about the Steers was the discovery of C.C. Risenhoover, a white Texan with the coloured touring team. Risenhoover even wrote a book on his adventures. In February, 2009, our Rich Necker tracked him down in Granbury, Texas:

One of the features which caught our eye about the Steers was the discovery of C.C. Risenhoover, a white Texan with the coloured touring team. Risenhoover even wrote a book on his adventures. In February, 2009, our Rich Necker tracked him down in Granbury, Texas:

". . . To my amazement, he welcomed my call to his home in Granbury TX and we rapped for a good half hour. I even learned that his first given name, "Carmel", was a name selected by his mother in reference to the biblical Mount Carmel in Israel and that his middle name "Credille" has French origins. As a kid and even during his tour into Canada, friends and teammates always called him "Candy" as his early peers hung that moniker on him, equating Carmel with caramel. He mentioned that he was one of four pitchers on a roster of 12 players that barnstormed in 1954 through South and North Dakota, amongst other states in the mid-west, on their journey into Canada. He said that he recalled the team playing in Sioux Falls SD and Minot ND while in transit to Saskatchewan and that he thought the team had played games in Moose Jaw (no record of such in the Moose Jaw Times-Herald) and Saskatoon (again, absolutely nothing in the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix). One of his fondest memories of Saskatchewan, besides the overwhelming number of ducks that he saw along the wayside, was a meal of roast pork, mashed potatoes and gravy (at a rural boarding house) that he and his teammates had the pleasure of devouring after enduring an infrequent meal schedule (usually once a day) wherein an over-abundance of chicken fried rice, ketchup and crackers was the norm.

. . . He was much younger than his mates as, for the most part, they had been veteran players from the then-defunct Negro American League who had been brought in as ringers. Anyway, with his help, I was able to clarify names and positions played for those he recalled. One other recollection of his summer is pitching a 17-inning game in Canada before losing 1 - 0. Probably, the most surprising revelation evolving from our discussion was his admission to something that I had known nothing about. As he was planning on returning to complete his senior year in high school in Jasper and did not want to jeopardize his eligibility to play high school football and basketball, he used an alias, "Randy Keegan", in his role as a paid semi-pro baseball player that summer. Many years later in his fictional novel, "White Heat", he re-created his alter-ego in the form of "Randy Joe Keegan", a white pitcher on an otherwise all-black semi-pro team . . . Since he was unable to supply all the names on the complete 12-man roster, he referred me to a friend who still resides in Jasper and who knew many of the players on the Steers' teams over the years.

. . . I have since phoned his old friend, Arthur Neil Davis, and was able to update the names and spellings further . . . As well, Mr. Davis advised me that one of the few remaining players . . . was a retired high school principal / assistant school superintendant who used to play the hot corner and who still lives in Wiergate,TX . . . former third sacker Ray Lacey is well educated, very articulate and has an exceptional memory. In no time after our conversation began, we finished off the complete roster . . . Ray couldn't remember specific names of venues where they played but, like Risenhoover, he mentioned . . . the city of Moose Jaw as playing-manager Charlie Nichols' favorite. Not that they spent much time there but primarily because of the hospitality and friendliness of the people. In fact, he commented on the fine treatment the team received in Saskatchewan as the thing he remembers most fondly about the trip. On the flip side, he related a story about the near-miss the team had when their not-so-well-maintained bus, after crossing the border into the U.S on their way home, lost its brakes while descending a steep hill and, miraculously, didn't roll over or collide with anything. He went on to describe it as the most frightening thing that had occurred in his lifetime, even more so than during his wartime service in the military. He categorized the group of 12 players as a "great, great ball club" and felt that "Candy" Keegan was an unusually gifted high school talent. After listening to Ray mention that they sometimes would play 3 or 4 games in a day (and in different locales), I have a feeling that they were playing in mostly rural areas without media coverage. Ray later played in eastern Canada with the Brantford Red Sox and was a teammate of "Seabiscuit" Wilkes who passed away this past summer.

. . . So, here's the skinny on how the complete 1954 Steers' 12-player roster should actually appear . . . Brown "Cut" 2B, Hicks Vernon CF, Jackson Alvin LHP, Johnson Johnny LHP, Jones John Henry C/OF/RHP/IF, Lacey Ray 3B, Nichols Charlie "Nick" SS/OF/mgr, Powdrill Vernett OF/C, Risenhoover Carmel "Candy" (played using the alias Keegan Randy) RHP, Robison O. B. LHP, Snoddy Tom 1B, Williams Roy C/3B/OF.

Matt Faye, Beaumont Enterprise, Feb 28, 2024

Seven years before baseball was desegregated in America, a black logging contractor in Jasper started his own team.

Elmer Simmons was known as the wealthiest black man in Jasper during the early 1940s. He spent his money on the sport he loved, building a stadium in town that rivaled any throughout Southeast Texas.

Over the next two decades, his Jasper Steers club became a staple in the region, competing against teams far and wide as one of many independent Black semi-professional baseball teams in the U.S. at the time. The Steers played against mostly-white minor league teams and other all-Black independent clubs.

A historical marker on Steer Stadium Road just off U.S. 190 in Jasper is all that remains of the once great venue. However, the team's local legacy lives on, according to Jasper County Historical Museum Director Tod Lawlis.

"The Steers are an important part of Jasper's story," Lawlis said. "It's one of those things that will always have a connection in the community."

Simmons first started the team by buying bleachers, lighting, dressing rooms and concession stands from a defunct baseball team in Lake Charles. The facilities were shipped and reassembled as Steer Stadium, which hosted the team's home games throughout its existence.

Local fans were drawn to the baseball spectacle. Betty Holmes Williams recalls going to games with her father during the Steers' later years. They would sit on the three-tiered wooden stands with the team bus not far from view in the parking lot.

"These times are some of my favorite memories," she said.

But Simmons loved taking his team on the road, too. The all-Black squad often travelled to different states for games and even had a documented trip into Canada that showed off their talents to a new audience.

In the mid 1950s, Steers Stadium also hosted games for the Jasper Bulldogs, the town’s high school baseball team for white students. Prior to the game, Simmons offered a Steers roster spot to one of Jasper's white pitchers, C.C. Risenhoover.

Risenhoover performed well in the game and proceeded to spend the next summer travelling around the country with the Steers as their only white player. He published a book in 1992 about the experience titled "White Heat."

The Steers played their last game as a team in 1961. By this time, the color barrier had been broken in professional baseball, and there were more opportunities for Black players to enter professional leagues. Jackie Robinson integrated professional baseball as a Brooklyn Dodger in 1947.

A Texas historical marker was placed at the site of Steer Stadium in 2015.

Lawlis said the Jasper County Historical Museum is working to recreate its exhibit dedicated to the Steers team. The museum has undergone multiple changes since Hurricane Laura destroyed its roof in 2020.

"We've tried to refocus our museum to really put Jasper at the forefront," Lawlis said, "and the Steers are certainly included in that."

Carlton Stowers, Dallas Observer, April 3, 2003

White Heat

It is a warm and lazy East Texas summer a half century ago that author and former SMU journalism professor C.C. Risenhoover most fondly remembers--long before the 1998 dragging death of a black man named James Byrd Jr. chilled and repulsed the nation and turned the logging community of Jasper into a pitch dark example of hate-crime ugliness.

In 1954, segregation was still very much a part of the social climate with blacks and whites attending separate schools and churches. African-Americans were directed to avoid public drinking fountains and rest room facilities reserved for "whites only," and allowed to view Saturday-afternoon matinees only from the balcony after entering the movie theater through a side door. In the downtown Jasper cafe where Risenhoover's mother worked as a cook, the few black customers who boldly stopped in for lunch or a cup of coffee were directed to a tiny back room adjacent to the kitchen.

While the young Risenhoover was aware of the color line that divided the community, he gave it little thought. It had no real effect on him. After all, many of his childhood friends, neighbors living just across the railroad tracks in the tiny houses furnished by the local sawmill, were black. With youthful pals who had nicknames like Biscuit, Capjack and Iron Man, he played sandlot ball, swapped stories and hunted squirrels in the cypress-shaded bottomlands.

It was not, he admits, until he was a teen-ager that he became firsthand familiar with some of the difficulties that African-Americans, young and old, experienced. Now, it is that long ago awakening that award-winning, Atlanta-based Triple Horse Entertainment is making plans to bring to the screen as a theatrical movie to be titled Outside the Lines.

"This," says Triple Horse producer Karl Horstmann, "is a powerful story that is going to be highly entertaining yet deal with many of the issues our society is still struggling with." First told in autobiographical book form by Risenhoover, it is an understated tale of racism and redemption, coming-of-age and the pursuit of a boyhood dream, told in a semi-pro baseball setting where a barnstorming group of men and boys--11 of them black, one white--play for the love of the game. And each other.

Son of a sawmill employee, Risenhoover was just 16, looking ahead to his senior year at Jasper High School and dreading another summer working on a logging crew, when a life-changing opportunity came his way.

"There was this guy in town named Elmer Simmons, a pulpwood contractor, who was easily the wealthiest black man in Jasper," Risenhoover says. "He loved baseball and had put together a touring semi-pro team that was mostly made up of former Negro League players who he'd hired to work for him.

"He'd even gone somewhere and bought all the fixtures--bleachers, lighting, dressing rooms, concession stands--from an abandoned minor league stadium and had them moved to a plot of land he owned just outside the Jasper city limits."

It was there that the all-black Jasper Steers played their home games. And it was there, in that summer of '54, Simmons promoted an exhibition game matching his team against an all-white minor league team from nearby Lake Charles, Louisiana. Determined to draw the largest number of paying customers possible, the inventive Simmons approached Risenhoover and his lumber inspector father with a proposition: If C.C., a youngster who had been thrilling Jasper High baseball fans with his fastball and sharp breaking curve since his freshman year, would pitch in the exhibition, he'd earn $50.

"I think," Risenhoover says, "that he felt having a white pitcher on the field with eight black teammates might be the kind of novelty that would help draw a crowd. For me, it was just an opportunity to play another game, to pitch against some batters more talented than I'd ever faced." His father, once a gifted pitcher for the Broken Bow, Oklahoma, "town team" before going off to World War II, gave the idea his blessing.

Despite running a high fever on game day and occasional racial catcalls from the stands, young C.C. performed well. He pitched 13 innings, registered 22 strikeouts, and he and the Steers won, 3-2. The postgame celebration, however, was short-lived. That night he was admitted to the hospital where he was diagnosed with a severe case of bronchitis.

"I was still in the hospital when Mr. Simmons visited me and said that the Steers would soon be leaving on a summer tour that would take them all the way into Canada," Risenhoover says. "He asked if I would like to sign on as one of the team's pitchers. When he told me he'd already cleared it with my parents, I immediately agreed."

He quickly learned that in semi-pro baseball, the emphasis was definitely on the "semi." Each of the 12 players on the team would, according to their contracts, receive $2 per day for meals and a small percentage of the gate receipts should any money be left over after travel expenses. In truth, there were days when even the two bucks for food wasn't passed out.

"We'd usually eat only one meal a day," he says. "And most of the cafes where we ate probably hoped they'd never see us again. We'd go in, order bowls of chili, doctor them up with all the ketchup we could find and eat every cracker in the place. Then, of course, we never had any money left for a tip."

The ancient old team bus, with "Jasper Steers" painted on its side, often clattered through the night to make it to the next day's game. "We started out playing all over Louisiana and Texas, then up through Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, North and South Dakota and into Saskatchewan, Canada," says Risenhoover, now making his home in Granbury.

It would be a rare treat when the team was allowed the "luxury" of spending a night in some ramshackle "colored town" hotel. There, the players often slept on broken-down beds with stale-smelling mattresses that were covered with unwashed sheets. When nature called, a trip to the outhouse was the rule. Still, it beat trying to rest on the side of some dark road and bathing in creeks and rivers, which Risenhoover and his teammates often did.

"But it was never about accommodations or money," Risenhoover, now 66, says. "It was about having the opportunity to play baseball. Everyone on that team loved the game and was thrilled to get the chance to play every day. Some were dreaming of getting a shot at the big leagues, like Jackie Robinson had just a few years earlier." In truth, the only success story was that of teammate Alvin Jackson, a left-handed pitcher who went on to pitch for the Pittsburgh Pirates and New York Mets, then served for a while as the Boston Red Sox pitching coach.

"But for most, playing for the Steers was just a way of staying in the game for another season or two."

For Risenhoover, that summer when he and his teammates played in big cities and rural whistle stops, when his windups were occasionally made as the chants of "white boy" and "nigger lover" echoed from the stands, it was a learning experience that would remain with him for a lifetime. "I gained a valuable understanding of what it was like to be a minority," he says. Most treasured of his memories of the tour, however, was the manner in which his teammates accepted him. "I don't think I'm exaggerating when I say that our defense seemed to play just a little bit harder when I was pitching. Maybe it was because they were worried about me being too young to stand up to the kind of hitters I faced. But I like to think they did it because they respected me as a teammate."

Certainly, the youngster pulled his weight. He doesn't remember his won-lost record, but points out that the Steers rarely lost. "We were sort of a baseball version of the Harlem Globetrotters," he says. It is, however, one of the team's rare defeats that he can still recall. Playing against a Canadian all-star team at the end of the June-to-August tour, he pitched 17 innings before losing 1-0.

By the time he returned home, Risenhoover's arm would never be the same. His own dreams of big league glory ultimately fell short after disappointing spring training tryouts with the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Kansas City Athletics.

For that memorable summer, once all the gate receipts were tallied and operational expenses deducted, the young pitcher pocketed the grand sum of $250.

It would be years, long after his playing days were over and his attention turned to writing and teaching the craft to others, that he recalled his summer with the Jasper Steers in his 1992 novel White Heat. Though it enjoyed good reviews and modest success in the marketplace, it had long been out of print when a friend passed along a well-worn copy to Triple Horse producer Horstmann, himself a one-time semi-pro catcher.

Having just won a 2002 Atlanta Film Festival award for a short film titled Cliché that he'd written, directed and produced, he was anxious to do a feature-length film. "I couldn't get the story of this kid playing with the Jasper Steers out of my mind," he says.

Nor, for that matter, has Risenhoover. "You know, when James Byrd was dragged to death by those guys, I felt terrible. Not only for the horrible thing that happened to him and his family, but for the entire community. Jasper's a good place to live, with a lot of good people. The town and its people didn't deserve to be portrayed the way they were.

"The story of the old Jasper Steers, I hope, will show another side of my hometown."