Richard "Dick" Brookins

Born : July, 1879 in St. Louis, Missouri ?

Third baseman

Vancouver Beavers 1909

Regina Bone Pilers 1910

The Brookins Banishment - a stain on the reputation of the W.C.B.L. By Rich Necker

The Regina Bone Pilers, under the direction of new manager Louis “Roxey” (often spelled as “Roxy” in the Regina print media) Walters, entered the 1910 pre-season at their spring training base in La Crosse, Wisconsin full of enthusiasm and optimism. Following a disappointing 1909 campaign in which the Reginans had finished sixth, wholesale changes had been made and a number of veteran players, with supposedly solid baseball backgrounds, had been added to the mix.

One of these was journeyman third baseman Richard “Dick” Brookins, then approaching thirty-one years of age. While much of his background remains unclear, his experience is known to have included three seasons in sanctioned leagues, commonly referred to as “organized baseball”. Between 1906 and 1908, Brookins played on a regular basis in the Wisconsin State League, the Northern Copper  County League and the Northern League, all designated as Class D level baseball. As well, there were reports that he had begun the 1909 campaign with the Vancouver Beavers of the Class B Northwestern League, but had been cast aside when it had been suggested that he was a man of colour. Walters and Brookins had been teammates for part of the 1907 season with the Green Bay Orphans of the Wisconsin State League and the rookie manager appeared to have the utmost confidence in skills exhibited by his former club mate.

County League and the Northern League, all designated as Class D level baseball. As well, there were reports that he had begun the 1909 campaign with the Vancouver Beavers of the Class B Northwestern League, but had been cast aside when it had been suggested that he was a man of colour. Walters and Brookins had been teammates for part of the 1907 season with the Green Bay Orphans of the Wisconsin State League and the rookie manager appeared to have the utmost confidence in skills exhibited by his former club mate.

It's believed Brookins, thought to have been a light-skinned African-American, had been able to avoid detection as an unwanted species in organized baseball by, initially posing as one of caucasian ethnicity and later, passing himself off as a native American Indian which, in that era of Jim Crow legislation, placed him slightly higher in the hierarchy of baseball apartheid.

Right - Third baseman Brookins is identified as one of two "Red Men" on the Green Bay team (Eau Claire Leader, May 18, 1907)

Those of aboriginal background were usually tolerated with the assumption being that they could be “civilized” into the white culture of the day. On the other hand, blacks faced extreme discrimination and total exclusion.

Quite frankly, no one knows for certain Brookins’ actual racial heritage. There appears to be no record that he had ever spoken out on the issue.

Census records from the first decade of the twentieth century list the racial origin of his family as being white. In a 1999 article in the "National Pastime", Bill Kirwin (founding editor of "Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture") maintains that it was not until Brookins’ 1908 stint with the Fargo club in the Northern League that this part of his background was seriously challenged. Although a newspaper article from Hannibal, Missouri labeled him as “a Negro”, North Dakota fans and press generally chose to ignore the claim and give Brookins the benefit of the doubt. The dispute had little time to simmer as the season ended prematurely with the collapse of the circuit.

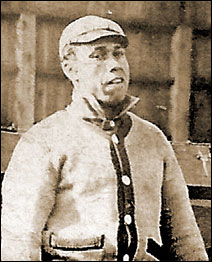

Once pre-season play began for the 1910 Bone Pilers, Brookins was being sold to the public as an American Indian. Contrasting claims were made as Bone Piler manager Walters went on record as stating “Brookins was of Puerto Rican and French ancestry”, an assertion that was divergent with that of the Regina executive and press, both of which identified their third sacker as being “one of the noble red men”. That he did not possess the dark pigmented skin normally associated with those of black heritage is generally accepted. I've come across just two photos of Brookins, the one above from the Regina Morning Leader of April 12, 1910 and the other, below, from a postcard featuring the 1909 Vancouver Beavers.

Whether the Regina management was fully cognizant of the resistance that they would be facing in bringing Brookins to western Canada, we will never know. In any event, their press releases out of spring training consistently portrayed him as being an American Indian. In the same April 12, 1910 edition of the Regina Morning Leader, the caption under Brookins’ photograph reads: “hard hitting Indian who will hold down the awkward corner.” Manager Walters was certainly impressed enough to make the following statement in the April 27, 1910 Regina publication following a spring training exhibition game in Winona, Minnesota: “Brookins fielded in great form, making two or three sensational plays.” Needless to say, his pre-season performance was sufficient to earn him a starting spot on the roster at the hot corner.

Early in the season, rumblings began to be heard from some of the member teams. One newspaper, however, was sympathetic toward the plight of the Regina player but only as far as it related to equality with aboriginals. The following was printed by the Moose Jaw Evening Times in their May 6, 1910 paper: “Word has been received yesterday at league headquarters that Medicine Hat and Calgary clubs had protested Brookins of Regina on the ground that he has Negro blood in his veins. Is this right? So long as the Negro is accepted to citizenship, why should he not have equal rights with the Red Man on the diamond?”

Nevertheless, the prevailing sentiment was similar to that expressed within the following excerpts from the Calgary Herald of May 12, 1910: “There is some talk of Brookins the third baseman of Regina being protested on the grounds that he is a colored man.” Next from the same reporter came a revelation that Brookins had apparently been in western Canada the previous season only to be sent packing. Picking up on his dialogue: “ Last season Brookins was with Vancouver the early part of the year and the same trouble arose, the result being that Brookins was released by Vancouver.” Summing up his remarks, the same scribe went on to adopt the following stance: “According to the rules of the national agreement , colored players are barred in organized baseball and, if Brookins is a colored man, as he looks to be, his case should be no exception to the rule.”

The allegation that Brookins had been the target of similar treatment in western Canada during the early 1909 season while playing in the Class B Northwestern League was particularly intriguing as this was the first and only time that such a development had been mentioned in any of the writings I had encountered dealing with his baseball career.

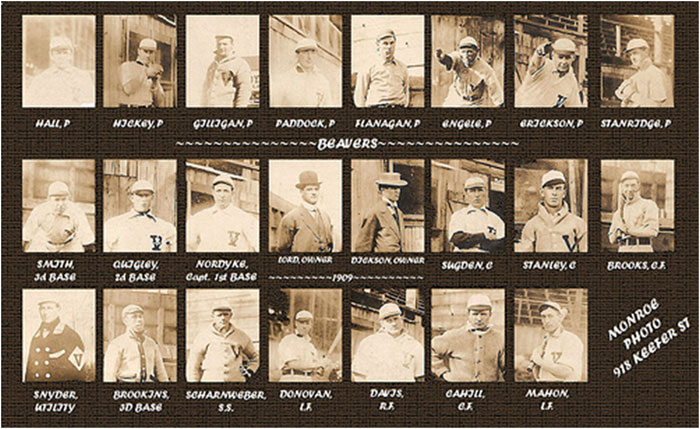

My curiosity spurred, I began to investigate the validity of the claim. Upon checking the early season roster of the 1909 Vancouver Beavers, it came to light that at least six members of that coast city squad (third baseman Wally Smith, second baseman Bill Quigley, catcher Matt Stanley and pitchers Jack Hickey, Del Paddock and Pete Standridge) wound up playing in the 1910 W.C.B.L. and would have had first-hand knowledge of what had transpired the prior campaign. It seems likely the Calgary Herald reporter was probably one of those privy to what had occurred, especially given that four of the aforementioned six players wound up as members of the 1910 Bronchos.

Through sheer luck, I stumbled onto an internet image of a postcard featuring pictures of the 1909 Vancouver Beavers. Sure enough, Brookins’ photo appears in the bottom row, second from the left with the position notation of third base. Only sparse coverage of the Beavers’1909 spring training exploits made it to the sporting section of the Vancouver Daily Province that April. In only one pre-season edition (Monday, April 12th) was Brookins’ name mentioned, a reference that he was being temporarily inserted at second base after a series of injuries to Vancouver's regular middle infielders. It was evident in the writings from their training base in Washington state that he did not figure to be a regular position player for the Beavers and that he seemed to be vying for, at best, a utility role on the squad. As a career Class D player, perhaps the elevation to Class B level play was not totally within his grasp. Nevertheless, he began the season as part of the allowable 20 player roster (see the postcard image above). By league rules, the roster eventually had to be trimmed to 15. Vancouver's other daily newspaper during that era, the Daily World, also had scant coverage of Brookins. In its April 19th publication, the paper published an article on the "Cherokee" infielder:

Through sheer luck, I stumbled onto an internet image of a postcard featuring pictures of the 1909 Vancouver Beavers. Sure enough, Brookins’ photo appears in the bottom row, second from the left with the position notation of third base. Only sparse coverage of the Beavers’1909 spring training exploits made it to the sporting section of the Vancouver Daily Province that April. In only one pre-season edition (Monday, April 12th) was Brookins’ name mentioned, a reference that he was being temporarily inserted at second base after a series of injuries to Vancouver's regular middle infielders. It was evident in the writings from their training base in Washington state that he did not figure to be a regular position player for the Beavers and that he seemed to be vying for, at best, a utility role on the squad. As a career Class D player, perhaps the elevation to Class B level play was not totally within his grasp. Nevertheless, he began the season as part of the allowable 20 player roster (see the postcard image above). By league rules, the roster eventually had to be trimmed to 15. Vancouver's other daily newspaper during that era, the Daily World, also had scant coverage of Brookins. In its April 19th publication, the paper published an article on the "Cherokee" infielder:

"Dick Brookins, a candidate for the infield, will be given a trial in one of the games this week. He worked out on Sunday and made a great impression. He is a full blooded Cherokee Indian and has played in the Northern League where he was one of the best."

That brief item was the only time his name wound up in print in the 1909 Daily World. The Beavers opened the schedule with a nine game series as visitors in Tacoma. Brookins name never appeared in a single box score during that series as he was saddled either with the role of a uniformed bench warmer or else was sitting in the stands as a non-dressed taxi-squad member.

Once the club returned to the friendly confines of British Columbia's lower mainland on the steamboat "Iroquois" for their home opener against Aberdeen, Vancouver management announced that he would be getting his shot as a starter. The Tuesday, April 27th Province printed sub-headlines which read “Brookins To Get Trial” followed by “Indian Will Be Tried Out At Third Base In Opening Home Game.” The same article also emphasized that at least five player cuts were forthcoming in order to reach the allowable player limit. In spite of all the pre-opener hype, however, Brookins remained on the bench and no explanation was offered in the following day’s edition as to the reason for the change in plans. In the third game of the series, played on April 29th, he made his first and only appearance in a regularly scheduled Northwestern League game as he pinch-hit, albeit with unsuccessful results, for Beavers’ pitcher Jack Hickey in the 9th inning of a 6 to 1 loss to the Aberdeen Black Cats. After that lone appearance, his name disappeared altogether from the sports section of the Province. His quiet release was never publicized in the either of the aforementioned Vancouver papers nor was there ever any reference made to a racial concern by league officials or from member teams within the circuit.

The following season, 1910, Brookins is in the lineup of the Regina Bone Pilers. The club got off to a quick start during the first week but tailed off during the remainder of the initial month. Brookins participated in all 21 games that Regina played between May 4 and June 1 (several had been postponed due to rain and wet grounds) and always batted third in the lineup, suggesting manager Walters’ confidence in him as a hitter. Results, however, showed he wasn’t tearing the cover off the ball. Box scores of every Regina game up to the first of June, showed 15 hits (including 3 doubles and a triple) in 67 at bats for a .224 batting average. Offensively, he was known to be a daring baserunner while defensively, his play seems to have been inconsistent in spite of some spectacular performances at the hot corner.

Brookins and Walters came under heavy taunting and verbal abuse whenever and wherever they appeared on the road. Moose Jaw fans were particularly abrasive toward Brookins in an early season series played in the Mill City. Brookins, however, never seemed to lose his cool and appeared to take it all in stride. The Regina Morning Leader (May 17, 1910) responded to the continuing attack by commenting as follows: “You ought to hear the epithets hurled at our manager Roxy Walters and also at Dick Brookins, one of the most gentlemanly little ball players that stepped on the field.” The report went on to state that the Regina club intended to stand by Brookins, “their Indian third baseman”, to the finish. What was particularly interesting about this column was the writer’s strong conviction that the Negro allegations were totally false. The scribe went on to say “in fact, Brookins has in his possession a certificate to show that he is a graduate from a United States College for Indians.” Nonetheless, the Moose Jaw club went ahead and entered a formal objection to Regina playing Brookins at a league meeting held in Medicine Hat on May 16, 1910 (Moose Jaw Evening Times, May 17, 1910).

While the Reginans were on an Alberta road trip during late May and the first couple of days of June, things came to a head as a result of the imminent firing of Lethbridge manager Chesty Cox. The Lethbridge skipper, fully aware of what was about to happen, made a verbal deal to sign on with Regina. The June 2, 1910 edition of the Medicine Hat News reported the happenings as follows: “Chesty Cox has been let out by Lethbridge and catcher Lynch installed as manager. Cox was immediately signed on by Regina and played with the latter team against his old club mates on Tuesday night” ( May 31). As his final act in Lethbridge, Cox attempted to release one of his better players, first baseman Harold O’Hayer, so that the Bone Pilers could pick him up as well. According to Regina manager Walters (Regina Morning Leader, June 4, 1910), a vendetta ensued as the Lethbridge owner got wind of the skullduggery and vowed revenge in the form of having Brookins ousted from the circuit. With the support of the Medicine Hat magnate, a protest was lodged with league president C. J. Eckstrom (just as often spelled as Eckstorm in the print media of the day) of Lethbridge (on what grounds there seems to be nothing definitive in print other than the racial issue).

On the basis of the complaints received, president Eckstrom referred the matter to the National Association for a ruling. The Commission looked into the matter and found no dispute with Brookins’ eligibility. An unsolicited letter to the Regina Morning Leader from J. M. Cummings, editor of “The Sporting News” was printed on May 26, 1910 and in its contents, Cummings was quoted as writing: “If the National Association has not barred Brookins for alleged Negro blood, the matter will be strictly up to the Western Canada League for adjudication.” Cummings went on in his letter to claim that “Brookins’ people are well known residents of St. Louis (ed. note - presumably Missouri although the Ancestry.com website, using information from the 1920 U. S. federal census lists a Richard Brookins, born about 1880, of St. Louis in the state of Minnesota), live in a neighborhood exclusively for whites and are classed as white.” With the matter now back in the lap of Eckstrom and, without a ruling from the National Commission to back him up, he bowed to the pressure and declared Brookins as being ineligible for further play. Regina manager Roxy Walters stood by his player and was defiant of Eckstrom’s edict.

On the basis of the complaints received, president Eckstrom referred the matter to the National Association for a ruling. The Commission looked into the matter and found no dispute with Brookins’ eligibility. An unsolicited letter to the Regina Morning Leader from J. M. Cummings, editor of “The Sporting News” was printed on May 26, 1910 and in its contents, Cummings was quoted as writing: “If the National Association has not barred Brookins for alleged Negro blood, the matter will be strictly up to the Western Canada League for adjudication.” Cummings went on in his letter to claim that “Brookins’ people are well known residents of St. Louis (ed. note - presumably Missouri although the Ancestry.com website, using information from the 1920 U. S. federal census lists a Richard Brookins, born about 1880, of St. Louis in the state of Minnesota), live in a neighborhood exclusively for whites and are classed as white.” With the matter now back in the lap of Eckstrom and, without a ruling from the National Commission to back him up, he bowed to the pressure and declared Brookins as being ineligible for further play. Regina manager Roxy Walters stood by his player and was defiant of Eckstrom’s edict.

Under the caption “Regina Forfeits Game”, the Edmonton Daily Bulletin of June 3, 1910 described the events in this form: “Tonight’s game was forfeited by Regina to Medicine Hat. Walters, refusing to play without Brookins, the alleged Negro who has been barred from the game by president Eckstrom. Umpire Wheeler received a wire from the president giving explicit instructions that Brookins was not to play. Walters pulled his team off the field and became liable for the $50 fine which the president has stated that he will impose on managers taking such action.”

[Right - Brookins' cartoon as carried in the Manitoba Free Press, May 27, 1910]

Newspaper articles supportive of Brookins and critical of Eckstrom’s stance began to appear. “Brookins has broken none of the rules of the league, his behavior in fact has been exemplary” decried the Morning Leader on June 3, 1910. A Winnipeg Free Press writing reprinted in the June 6 Regina publication went on to question Eckstrom’s judgment as follows: “It would be interesting to know how far president Eckstrom had investigated the case before putting the ban on the best third baseman in the league and one of the most gentlemanly and cleanest players that has ever appeared in a uniform in the Western Canada League.” A Regina Morning Leader article of June 15, 1910 entitled “Execution Before Trial” seems to summarize the feelings of those within the Regina camp. The paragraph points out that secretary A. L. Smith from the Regina executive had received a letter from league president Eckstrom in which he had admitted that he was still seeking evidence to consolidate his position in disqualifying Brookins, the premise being that such was akin to hanging a man and then trying him afterward.

Following his banishment from the W.C.B.L., Brookins returned alone on the train to Regina, his ex-teammates still in the midst of their road swing through Alberta. Just before he left for the United States, a report surfaced in the Regina Morning Leader of June 7, 1910 stating that “The Indian has accepted the situation in the stoical manner natural to his race.” Once he exited the Queen City, he seemed to fade into anonymity, more than likely playing as an obscure itinerant pick-up. There is no known record of him ever playing again in organized baseball. As for the Bone Pilers, they stumbled mightily after Brookins’ departure and finished dead last in both halves of the W.C.B.L. campaign, eventually declaring bankruptcy and folding with seven games remaining in their schedule.