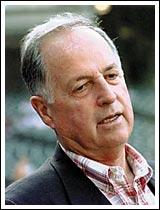

Lawrence Patrick Gillick

6'1", 185, Bats Left, Throws Left

Born : August 22, 1937, Chico, CA

(Vulcan Elks, Granum White Sox,

Edmonton Eskimos, 1956 to 1958)

Gillick spent five years as a player in the Baltimore farm system before deciding his career was to be in baseball administration. He earned his spurs as an assistant farm director with the Houston Colt .45's in 1964 and 1965 before taking on a more involved role as a scout with Houston. Eventually he became Scouting Director of the Astros in 1974 and then with the Yankees in 1975-76.

A move north in 1977 proved highly successful for both Gillick and his new club, the Toronto Blue Jays. As General Manager of the franchise, he guided the new squad through expansion to back-to-back World Series championships in 1992 and 1993. More success followed - in Baltimore, 1996 to 1998, and Seattle 2000 to 2003. He moved on to the Phillies in 2006 and ended up with his third World Series title, before retiring (again).

W-L ERA G IP H R ER BB SO

1956 Vulcan, FWL N/A

1957 Univ So. California 0-1 1.80

1957 Granum, FWL N/A

1958 Edmonton, WCBL 0-3 10.41 8 32 47 38 37 29 27

1959 Stockton, California 9-5 3.78 38 162 152 82 68 127 127

1960 Fox Cities, I.I.I. 11-2 1.91 19 132 114 35 28 67 135

Vancouver, PCL 1-6 4.28 7 40 43 28 19 27 29

1961 Little Rock, SA 10-7 4.38 33 152 139 83 74 102 113

1962 Elmira, Eastern 7-5 3.13 20 112 92 42 39 62 90

Rochester - Columbus, IL 2-4 6.50 11 36 47 27 26 30 26

1963 Elmira, Eastern 5-3 2.25 33 88 74 33 22 53 76

Rochester, IL 0-0 1.29 3 7 6 4 1 6 1

1964

1965 Wichita Dreamliners, IND

(Interview with Pat Gillick, December 10, 2003)

Q: How did a California kid end up playing in Vulcan, Alberta ?

A: I was originally from Chico, California, about 90 miles north of Sacramento. In 1956, I would have been eighteen years old and I was going to go to college at Fresno State. Pete Beiden, who was managing at that time at Regina, got me to go to Vulcan. He had sent some Fresno State guys up there. When I got there, I had no idea where I was going. I said were in the middle of no-where really. There wasn't much in that town."

I ended up going to USC. At the last minute, Rod Deadeaux at USC offered me a scholarship. I was going to school in Los Angeles at LA Valley and just because SC was close I decided to stay in Los Angeles instead of Fresno State.

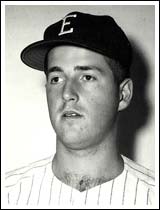

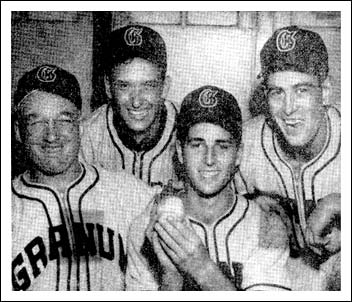

Young lefty Pat Gillick after his 4-hit, 17 K performance in the Calgary Tournament.

Young lefty Pat Gillick after his 4-hit, 17 K performance in the Calgary Tournament.

Manager George Wesley, bottom left, Tedd Bogal, top left, and Bill Fennessey. Gillick had earlier tossed a no-hitter in the Medicine Hat Tourney. (Lethbridge Herald, August 27, 1956)

"When Pat Gillick was playing for us [Vulcan] he didn't win a game ... but in the middle of the season George Wesley [of the Granum White Sox] picks him up to go up north somewhere to play in a tournament and he throws a no-hitter. Well that didn't sit too well with the people of Vulcan. The next time he went to the bank (to collect his pay), before they gave him the money, they asked, 'Did Wesley pay you?' When Gillick said yes, they said, 'We're docking that from your pay' And they did." (Greg Seastrom, Gillick's Vulcan roommate)

While Gillick had trouble getting in the win column for Vulcan, he was money in the bank on the tournament trial. Pitching for Granum, he tossed a no-hitter to win a spot in the finals in the Medicine Hat tournament. Two weeks later, Gillick pitched a four-hitter and fanned seventeen to give Granum top prize in the Calgary tournament. And, at Fernie, he pitched Granum to an 18-1 victory and a spot in the finals.

That's true! I was playing for the team in Vulcan, but played in those tournaments with George Wesley's team in Granum and basically they said if you're going to be playing with him you can draw half your salary from the Granum White Sox and half from the Vulcan Elks. My salary was $250 a month.

Q: Just how did you travel up to Alberta for the baseball season?

A: Actually, I hitch-hiked from LA to Alberta. Money was tight in those times and I was trying to save a little money. I took about four days. I got into Salt Lake and went up to Idaho Falls and into Helena and Great Falls and up through that way and just kind of hitch-hiked along the way.

Going away at that early age, being on my own, really made me grow up a bit faster. What really impressed me was the tournament competition. You knew it was sort of a do or die situation, either you won and went into the winners' bracket or you lost and you were out. It brought more intensity and more urgency to us early on. We had to be competitive game in and game out so it was a good experience for us.

Q: How do you reflect upon those times?

A: I had a great opportunity there. I played with Ron Fairly, I played with Lenny Gabrielson, with the Wesleys, Jim Lester. I mean there was a real competitive spirit, but a real friendship too and I've stayed in touch with some of the people over the years and you know it's almost fifty years gone by and it's nice to think of the times we spent. Very, very cherished memories.

Q: Why did you give up on your pro career? (Gillick went 9-5, 3.78 in his debut season with Stockton of the California League and had an 11-2 mark with a 1.91 ERA in 1960 with Fox Cities of the Triple-I loop. He moved up to the Triple-A International League before deciding to leave the playing field for the front office.)

A: The last year or two I had a little bit of arm trouble and I had kind of given myself five years and if I didn't make it then I was going to get out. That's what kind of made me change and move into administration.

Q: Did you know Bruce Gardner very well? [Gardner, a USC and WCBL star, shot himself on the mound at USC.]

A: He was my roommate. It didn't surprise me. I can recall the day. I was in New York City that day and I came down to breakfast somebody said, "Did you hear about Bruce Gardner?" I said no and he told me what had happened and it didn't surprise me because for Bruce it really weighed on his mind. He had an opportunity to sign with the Chicago White Sox out of high school and didn't take that opportunity and went to USC and I think that probably, that thing weighed on his mind more than anything I had ever run into. It really, really, really bothered him that he didn't sign out of high school as opposed to going to school and then signing. He was very intense. Absolutely. And, yes he sure had the talent to make it as a major leaguer. I just wasn't surprised to hear it because he just really couldn't get away from this thing at all.

With his early experience on the Canadian prairies, followed twenty years later by his triumphs as General Manager of the Toronto Blue Jays, Pat Gillick, became recognized as a great ambassador for Canada [so revered, he won induction into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 1997]. He has maintained his Toronto home since joining the Blue Jays in the mid 70s.

When came up in 1976 our daughter was quite young at the time and she went through grade school and high school and university and we just decided to stay here. The Blue Jays and Labatts gave me my opportunity in '76 and I felt there was a closeness and obligation to stay here and we did. We really enjoy the lifestyle and the people. It's been a real plus for us.

Gillick man with M's master plan

Seattle GM uses savvy, skill to put together baseball's best team

ROSS NEWHAN, LOS ANGELES TIMES

Originally published July 1, 2001

Pat Gillick has too much going for him as general manager of the runaway Seattle Mariners, too much going for him as a man who has produced winners at each of his GM stops, to look back and dwell on one that got away.

Only observers familiar with a little-known piece of Anaheim Angel history are left to wonder how Gillick might have transformed that beleaguered franchise if a group he fronted had purchased the team before Gene and Jackie Autry sold to Disney.

After all, Gillick's Toronto Blue Jays won five American League East titles and back-to-back World Series titles, his Baltimore Orioles reached the American League championship series in two of his three years there and his Mariners are on a fast track to a second consecutive playoff appearance despite the loss of Ken Griffey Jr. in his first winter on the job and Alex Rodriguez in his second.

As Brian Cashman, a man familiar with winning as general manager of the New York Yankees, said: "In our business, Pat Gillick is basically the architect of all architects. He wins everywhere he goes under just about every condition. Nothing he does surprises me any more given his success."

A graduate of the old school, Gillick, 63, has adapted to the big-money pressure that recently has made the general manager's office the domain of younger men and created volatile turnover in a job where there was seldom any.

"I always expect the seat I'm on to be a hot one, and I always try to be optimistic but realistic," Gillick said. "Sometimes you can be so optimistic that it clouds your judgment. If you had asked me what I expected of our team coming out of spring training I'd have probably said, 'Maybe a few games over .500.' I thought we'd have problems scoring runs. I was wrong. Now we're quite a few over."

It's still June, the Mariners are 35 over and -- despite recent vulnerability and the ongoing pursuit of another hitter (Chuck Knoblauch?) or pitcher -- have all but won the West as they continue a three-game series against the Angels in Anaheim. This is where Gillick, a homeboy who graduated from USC at 20, had hoped to set up residency when he and a group that included Bill DeWitt Jr., now a principal owner of the St. Louis Cardinals, met with Jackie Autry about buying the Angels in the fall of 1995.

"I thought the Angels represented a good situation and still do, but I don't think much about it any more or how anything might have been different," Gillick said.

Any synopsis of the Gillick story should include that he was a pitcher on USC's national-title team in 1958, spent five years pitching in the Baltimore farm system before accepting a front-office job with Houston, moved up through the farm and scouting ranks to become the Toronto general manager in 1977.

He would shake a reputation as Stand Pat, a man reluctant to trade, and successfully turn that expansion team into one that dominated the East. Gillick retired after the 1994 season, a year after the Blue Jays had won back-to-back World Series titles.

Gillick's wife owned an art gallery in Toronto and he was making good money as a Blue Jays consultant. He insists he wasn't looking for another job, but the prospect of running the Angels produced an itch too strong to ignore.

It was not long after the Angels talks collapsed, that he agreed to a three-year contract as general manager of the Orioles, lured essentially by the lobbying of Davey Johnson, a former minor league teammate who had already been hired by owner Peter Angelos as Orioles manager.

It looked like an ideal situation: a proven general manager and an owner who hated the Yankees and was willing to spend to beat them. The problem, however, was that the owner also thought he was the general manager, interfering in virtually every decision, charting his own course.

Johnson was fired by Angelos in his third year as manager. Gillick resigned when his contract expired. Angelos has since spent more for less than any owner in baseball. Gillick, after a year as chairman of the U.S. Pan-Am baseball team, accepted a three-year contract to replace Woody Woodward as general manager of the Mariners, stepping into a tenuous situation in which Woodward had already traded Randy Johnson under duress and Griffey and Rodriguez were coming up to free agency and one or both might have to be traded.

"I was aware of the situation generally," he said. "I wasn't aware that Griffey was so adamant about wanting to leave. I thought we could persuade him otherwise, but that wasn't the case. I also thought we had a competitive shot to keep A-Rod, but I wasn't aware that Texas would offer the ranch."

The Mariners won the wild card with a 91-71 record last year, beat the Chicago White Sox in the division series and lost to the Yankees in the ALCS. They then lost Rodriguez to Texas and bowed out of the high-stakes negotiations for Manny Ramirez before Gillick went another direction in trying to strengthen the offense -- signing Boone, importing Ichiro Suzuki and boosting an already strong bullpen with the signing of Jeff Nelson.

"How could anyone have envisioned this?," Gillick said. "I mean, if the Yankees are the yardstick, they won 87 games last year. We've simply had a lot things fall into place."

Winning, of course, is infectious, and the Mariners tend to feed off one another. Gillick suggests that the difference between 91 wins and a projected 118 has been the catalytic influence of Suzuki and Boone.

"I'd have been happy if Ichiro batted .280 to .300 and Boone put up decent numbers with good defense," Gillick said. "Now Ichiro leads the league in hitting and Boone leads in RBIs. They have far exceeded expectations. I'm not that good."

The Gillick File

- Age: 63.

- Hometown: Chico, CA.

- Playing experience: Five years in Baltimore farm system as pitcher.

- GM experience: Toronto 1977-94; Baltimore 1995-98; Seattle 1999-present.

THE MARINERS

Standing Pat no more, Gillick resigns

• The man who helped turn Seattle into a perennial playoff contender decides it's time to leave his GM job.

Kirby Arnold

For The Sun

October 1, 2003

SEATTLE -- Pat Gillick traded away Ken Griffey Jr., then built a team that came within two victories of reaching the World Series. He let Alex Rodriguez get the Texas Rangers' millions through free agency, then orchestrated tweaks to the roster that resulted in a 116-victory season.

The Seattle Mariners lost two of their biggest stars under Gillick, but they experienced unprecedented improvement with him as their general manager since the 2000 season.

The Mariners never achieved the one thing Gillick was aiming for, a championship, and after four years he decided not to try anymore.

Gillick announced Tuesday that he won't return in 2004.

"I had four kicks at the cat and couldn't get over the hump here, so I thought it might be a better situation if somebody else took a shot at it," he said. "We had four good seasons here and we didn't get where we wanted to be."

Mariners CEO Howard Lincoln said he made it clear to Gillick he wanted him back and tried the last two days to change his mind.

"I've been thinking about it for a couple of weeks," Gillick said. "But I kind of decided on Sunday."

Gillick, 66, will work as the GM until his replacement is hired, then serve the Mariners in a consulting role.

Mariners president Chuck Armstrong said the team hopes to have a new general manager hired by the end of this month. Major League Baseball discourages major announcements during postseason play.

The Mariners immediately began compiling a list of replacement candidates, including two longtime members of the current staff, assistant GM Lee Pelekoudas and player development director Benny Looper.

"That's what my goal has been," Looper said. "I've got a good background in the baseball side, in scouting and player development, and it's something I'm ready to try."

Roger Jongewaard, the team's highly respected scouting director who interviewed for the GM job four years ago, said he's not interested this time.

"It's what I've always worked for, but the timing just isn't right," said Jongewaard, 66. "It just kind of passed me by. I'm getting too old for that job. My life is changing and I'm doing what I'm interested in. I'm not quite ready to hang them up, but I'm getting close."

Gillick said he isn't immediately interested in becoming a GM for another club. He's under contract to the Mariners as a consultant for the next three years and, if he takes another job during that time, the M's would be entitled to compensation.

The Mariners won 393 games under Gillick, more than any other major league team the last four years. But the late-season failures the last two years, and the fact Gillick didn't make an impact move before the trade deadline, added a black mark to his legacy.

Gillick wasn't specific in his reason for leaving, although there has been a tug in Toronto since the day he took the Seattle job on Oct. 25, 1999. His wife, Doris, remained at their home there and he spent considerable time in Toronto, including the days before this year's trade deadline.

Gillick also refused to say he was inhibited by Mariners management in his efforts to improve the club during the season.

"I was able to wheel and deal enough," Gillick said. "Sometimes you want to be as free-wheeling as possible and for one reason or another you can't be that way. As far as any restrictions that prevented us from carrying out our jobs, I can't see anything."

The new general manager won't have quite the challenge Gillick did when he took over for Woody Woodward. Griffey had demanded to be traded, and Gillick swung a deal with the Reds that brought center fielder Mike Cameron, infielder Antonio Perez and pitchers Brett Tomko and Jake Meyer.

The Mariners also added first baseman John Olerud, relief pitcher Arthur Rhodes and utility player Mark McLemore and won the American League wild-card playoff berth in 2000, then took the Yankees to a sixth game before losing in the AL Championship Series.

The following offseason, the Mariners lost Rodriguez to free agency but Gillick signed relief pitcher Jeff Nelson and second baseman Bret Boone, a free agent after a sub-par year with the Padres.

The Mariners' next general manager must find the answer to the team's late-season swoon the last two years. Among the issues:

• He must find more power for the offense and at least one more left-handed relief pitcher.

• If Edgar Martinez decides to retire, the Mariners will need a new designated hitter.

• The new GM must decide which of the seven other free agents -- infielder Rey Sanchez, Cameron, McLemore, third catcher Pat Borders, and relief pitchers Shigetoshi Hasegawa, Armando Benitez and Rhodes -- should return.

• And he must decide what to do with third baseman Jeff Cirillo, who has shown no hope of performing in Seattle but is signed for two more years at about $15 million.

Pat Gillick: Baseball's best GM By Mike Berardino, Baseball America, May 2, 1994

DUNEDIN, Fla.--Why did the turtle cross the road? No one knows for sure. All Pat Gillick knew was that the poor creature was holding up traffic on one of those godforsaken two-lane roads in central Florida, and somebody had to do something.

So Gillick, general manager of the Blue Jays, one of the most powerful and successful sports executives in recent memory, got out of his rental car, walked past several equally perplexed motorists to the source of trouble, picked up the turtle and, dodging traffic from the opposite lane, carried it to safety.

This was several years back, sometime in the late 1980s, and Gillick had his wife Doris and daughter Kimberley in the car with him. Upon returning to the driver's seat, Gillick had a big smile on his face, the kind of self-satisfied, all-is-right-with-the-world grin you might have after slipping a five-spot to the old woman in front of you in the grocery line.

But no sooner had Gillick slid back behind the wheel than his wife spoke up with a shake of her head.

"Pat, you have to re-do it," she said.

"What do you mean?"

"Well, the turtle was trying to get to the other side. You brought him back where he came from."

By this point, traffic was moving again. It wouldn't be very convenient to stop the car, create another backup (not to mention a new symphony of honking), get out, grab the turtle--"It was a biggie," Doris Gillick says, "huge!"--and play Marlin Perkins.

But that's exactly what the GM of the Blue Jays did.

"An enigma," Blue Jays president Paul Beeston calls Gillick.

"Eccentric," Doris Gillick says.

"Compassionate," says Dave Stewart, the Jays righthander who joined the fold only last year.

To Stewart, a man of great compassion himself, the turtle tale isn't at all surprising. Unlike most successful businessmen, Gillick always seems to be looking out for others.

"Pat is straight with you, he's caring, he's approachable and he has no secrets," Stewart says. "You always know where you stand with him. Based on those things, he's a rare breed.

"I'll tell you this: Pat is the reason I ended up with Oakland."

Stewart smiles as he tells the story of how, upon being released by the Phillies in 1986, his agent called Gillick and asked if he was interested. Gillick said he was, but the Jays had enough young pitchers on their staff that the best they could offer Stewart was a Triple-A deal. As for a potential callup, he really couldn't make any promises.

But what about Oakland? The Athletics had pitching problems, and might afford the best opportunity to a 29-year-old journeyman facing the end of the line. Besides, wasn't Stewart from the Bay Area? Gillick made a call to Oakland GM Sandy Alderson, Stewart signed and the rest, including four straight 20-win seasons in green and gold, is history.

Whether scooping a wayward turtle off the pavement or saving a wayward righthander from baseball's scrap heap, Gillick loves the underdog.

That's just one of the traits people will miss when Pat Gillick, 56, retires after this season. There's also his honesty, creativity, humility and an uncanny memory. Many of his friends, coworkers and rivals don't understand the timing, but confounding people is a Gillick trademark.

After more than three decades in baseball management and 18 seasons at the helm of the Blue Jays' on-field operations, the architect of back-to-back World Series champions will step down as executive vice president for baseball. Gord Ash, his assistant for the past 10 years, is his choice to replace him.

"I feel good about it," the soft-spoken Gillick says of his decision. He originally announced it in January 1992, but many, such as Beeston and Jays manager Cito Gaston, say they'll believe it only when they actually see Gillick cleaning out his desk.

"I feel particularly satisfied with what this club has done," Gillick says. "People ask me about back-to-back, and I say it's great. But what pleases me even more is the 11 years in a row we've been over .500. That tells me we've done things the right way and been successful.

"So retiring in October doesn't weigh on me. If people aren't satisfied with their life and have goals they want to accomplish and dreams they want to realize, they shouldn't retire yet. But baseball has been very good to me, and it's time."

Gillick nearly retired last fall, shortly after the Jays became the game's first repeat champion since the 1977-78 Yankees. Chest pains had dogged him periodically for some time, but he always was willing to chalk those up to the stress and strain that accompany a sports executive during his 16-hour workday.

But the ante was raised when his doctor found a blocked artery. In mid-November, a day after throwing a surprise 80th birthday party for his mother in Arlington, Texas, Gillick flew back to Toronto and underwent an angioplasty.

"Pat only had the one blocked artery. The others were so clear you could drive a truck through them," says his mother Thelma Mineau, a retired actress. "As a rule, you don't have pain with blocked arteries. So the doctors felt he was very fortunate that he did have pain, and got to them right away before something bad happened."

It was only last summer that Ted Simmons, then 44, retired as GM of the Pirates after a heart attack. That and other incidents set Gillick to thinking.

"He's had some setbacks health-wise," says Jays vice president Al LaMacchia, along with Bobby Mattick one of two long-time scouting friends of Gillick who remain with the organization. "There's such stress and strain on him. He might have noticed himself getting irritable with people. He might notice this guy having a triple-bypass, that one a double-bypass. Those kinds of things make you think: Am I headed in that direction?"

So rather than tempt fate, Gillick will take a step back after this season. He's the first to admit he probably won't spend the rest of his days playing golf and telling stories. Type A personalities just don't do that. But he's looking forward to sampling a different lifestyle, one in which he won't be faced with so many deadlines and boarding passes and strange hotel rooms.

"I don't have any definite plans," Gillick says early one morning in his spacious but sparsely decorated office at the Blue Jays' minor league complex in Dunedin. "I really don't know what I'll do. Doris is nervous. I've always been a fairly active guy, and she wonders how I'll handle my new freedom. I'll think of something."

Learning to sail and obtaining his pilot's license are two challenges at the top of Gillick's retirement list. He'd also like to do some leisure traveling, to Europe (Italy, Belgium and his wife's native Germany come to mind) and the Caribbean.

For all his scouting travels, Gillick says he really hasn't done much sightseeing, unless you consider ballparks museums of a sort. Doris and Kimberley, a senior history major at Guelph University in Ontario, plan to help in that regard, with one proviso.

"I'd prefer that Pat not drive," Doris says with a laugh. "He drives terribly. I think he would have been a good cab driver. He's an energetic driver. I usually close my eyes so I don't have to watch what's happening."

Drag racing aside, there are plenty of ideas floating around inside Gillick's head. He could keep his hand in baseball and serve as a consultant to the Blue Jays or, following the lead of good friend and former boss Tal Smith, other teams as well.

He could wait for the next round of expansion and oversee ground-floor operations in a warm-weather climate like Phoenix, though he says that's unlikely given his age and the incredible debt forced upon such teams through expansion fees.

Minor league hockey is another option, as Gillick, a native Californian, has grown to love the Canadian pastime almost as much as the Maple Leaf-loving locals. There's also his idea--"my fantasy," he says--to bring hockey to inner-city kids.

"Inner-city black kids don't excel at hockey for economic reasons only," he says. "I think it would be interesting to see a whole team of city kids learn about the game and progress. That would be interesting. Maybe they couldn't play, but I don't see why they couldn't."

Hey, don't laugh. Gillick has set new standards for creativity in a career that began in 1963 as an assistant farm director under Astros GM Eddie Robinson. This is a guy who has done the unthinkable so many times he's rendered the word laughable.

See the signings of such supposedly unsignable prospects as John Olerud, Alex Gonzalez, Shawn Green and Danny Ainge.

"He has a very active imagination," Doris Gillick says. "He likes the challenge of doing something people say can't be done. If somebody says it can't be done, it's almost like he has to do it."

Gillick is the guy who turned the Mr. Wahoo award against the Indians. It was back in 1976, and Gillick, preparing for the expansion draft that would create the inaugural edition of the Blue Jays, was disappointed to see the Indians protect young catcher Rick Cerone.

"But look at this," Gillick told a roomful of scouts and assistants. "They didn't protect Rico Carty."

Eyebrows arched at the prospect of drafting a 36-year-old DH with bad knees. Peter Bavasi, then Blue Jays president, tried to blow off the idea.

"Rico was Mr. Wahoo," Gillick said to a roomful of blank stares. "Mr. Wahoo. The Indians man of the year. Let's take him. In Cleveland the writers and fans will kill the team if they lose Carty. Then they'll have to trade and get Rico back."

It happened exactly that way. The Jays took Carty in the first round, waited for the shock to set in along Lake Erie, then traded Carty back to the Indians for Cerone.

Gillick's baseball instincts are so sound, they may well have been genetic, as his mother suggests. His father Larry was a righthander who pitched for Sacramento in the Pacific Coast League for several years in the 1930s.

"Heck, Pat was nearly born in a ballpark," says his mother, whose acting career began at age 4 and whose credits include work with the "Our Gang" troupe, Bing Crosby and the Marx Brothers. "It was a 115-degree day in Chico, Calif., and Larry had to pitch that day. He dropped me off at the hospital and went ahead to the park. I think he lost."

Three months into motherhood, Thelma Gillick took a trip down to Los Angeles to visit her parents. She stayed a week and when she returned, Larry told her he wanted a divorce. She tried to talk him out of it, but it was no use. They had been married for five years and their young son was still sporting swaddling threads, but he'd made up his mind.

Larry Gillick's playing days ended not long thereafter, and he served stints in the Marines and the police force before he became sheriff of Butte County, 90 miles north of Sacramento. He held that position for more than 30 years, but with his ex-wife and son having moved to Los Angeles, his influence on Pat was minimal.

"Thank God Pat didn't turn out like his father," his mother says. "To meet him, you'd adore him. He was a real charmer. But you couldn't believe him for a second. I think that's why Pat's so darn truthful. His father used to lie to him a lot. He would say he was going to do this or pick him up at a certain time, and poor Pat would never hear from him."

That didn't stop Larry Gillick from hitting up his son for All-Star Game tickets or other goodies before his death in 1988. And what would Pat Gillick do when he picked up the phone and heard his absentee father on the other end of the line? Would he hang up in a huff? Of course not. Would he make the arrangements as if nothing ever happened? Did the turtle get across the road?

Young Pat gravitated quickly to sports, standing out the most at baseball and football. He reached the rank of Eagle Scout, and spent a great deal of time working with church groups as a devout Presbyterian. When he reached the fourth grade, Thelma pulled him out of public school--she was shocked they weren't teaching her son to write longhand.

"Military school brought some semblance of order to your life," Gillick says. "They gave you a lot of responsibilities. Things were expected of you. It wasn't catch-as-catch-can. I liked it."

He stayed there through the 11th grade, rising to the rank of captain, before the high school portion of the academy was dissolved. He transferred to Notre Dame High and teamed with another future sports executive, Bobby Beathard, on the football team. Gillick was the center and Beathard, now GM of the National Football League's San Diego Chargers, was the quarterback.

Gillick graduated from high school at 16, then went on to pitch for Rod Dedeaux' 1958 College World Series champions and obtain his business degree from the University of Southern California. A curveball pitcher without much velocity, Gillick didn't receive much interest from the pros upon graduation. He applied to law schools, and came close to enrolling at what now is Loyola Marymount University Law School.

But baseball still gripped him, so he headed off to Edmonton to pitch semipro ball in the Western Canada League. The Orioles signed him in 1959, and he bounced around for the next five years, moving from Stockton to Vancouver to Little Rock to Elmira to Rochester. Earl Weaver was his manager at three of those stops, which gave Gillick a lifetime's worth of stories about the feisty little man.

"Earl could give you a tongue-lashing, and an hour later it would be completely forgotten," Gillick says. "Earl had a very small doghouse, and he was one of the best handlers of pitchers ever."

Weaver also had quite a warped sense of humor. He must have derived considerable glee in pairing the teetotaling Gillick with all-time party animal Bo Belinsky as road roommates in Rochester. It also was Weaver who gave Gillick the nickname that endures to this day: Yellow Pages Pat.

Friends have since updated that to Segap Wolley ("Yellow Pages" spelled backward) as a way of teasing the human Rolodex, a veritable Rain Man who seemingly has more phone numbers at his disposal than the NYNEX book.

"Pat has a tremendous memory," LaMacchia says. "He just takes information and stores it in that bank in his head. He puts it back there in this little bank. It's like a vault or something. He recalls entire conversations he's had years ago. He can quote you things you said verbatim. It's uncanny."

Doris Gillick agrees--for the most part.

"He does have a fantastic memory of phone numbers," she says. "I don't remember any numbers. I don't have to. I just ask Pat. He can ask an operator in the morning for five or six numbers, then call the people at night, without writing the numbers down. It's incredible.

"That's with phone numbers. If I tell him something in the morning, he's forgotten it by lunchtime. That's different."

Gillick's career record with the Orioles was 45-32, 3.42. But when he came up with a dead arm in 1963, the organization released him and he was heartbroken. Law school again rose to the surface, as did several offers to coach at small colleges here and there.

But Gillick's life turned on a short, handwritten note from his mother, by then remarried to an engineer named Clyde Mineau, to an old friend in Houston, Eddie Robinson. It was Robinson who, along with Paul Richards, had scouted Gillick when they were with the Orioles.

"Eddie called me as soon as he got my note," Gillick's mother says. "I'd known Eddie since Pat was in college. He told me he always thought Pat was great executive material, and did I think he'd come to work for the Astros? I said I didn't know, but give Pat a buzz and find out."

After some soul-searching, Gillick decided to put law school on hold again, this time for good. He came aboard as assistant farm director, but he really did a little bit of everything.

"I got a feel for the whole operation," Gillick says. "Eddie was a little on the laid-back side. He liked to let you do your own thing. He wasn't always looking over your shoulder. He gave me an opportunity to put my finger in a lot of different areas: scouting, financial, personnel.

"He felt like I do. If you hire somebody, he has a job description. You have to give him the authority and room to do his job. If you're not going to let him do his job, then don't hire him. Do it all yourself, which is impossible."

Robinson and Richards were fired after the 1965 season, and a sharp young executive named Tal Smith was brought over from the Houston Sports Authority to run the Astros. Gillick was one of his inherited employees, and Smith admits it took the two men some time to become comfortable with each other.

But once that bond was forged, one of the great management combinations of that era was off and running. That's not to say there weren't any negatives.

"Pat can be exasperating," Smith says. "Doris or Bobby Mattick or Gord Ash would tell you the same thing. But he always has a way to quickly redeem himself. He senses when he's been exasperating, and he'll always make a quick call and make up for it that way."

For instance?

"Well, in Houston, you'd leave your office for a second and come back in, and Pat would be in your chair using your phone," Smith says. "That's just Pat, always active and involved. Or you'd be at your desk trying to get things done, and he'd come in with a question or an idea. It could get to be almost annoying.

"He's always probing, always investigating. That's what made him a successful scout. He's a quick study, and he's inquisitive. But at the same time, he has a tendency to get in the way. He does that to Doris at home. That's kind of his trademark."

While contemporaries such as Smith sometimes found Gillick a bit too much to take, his elders on the scouting trail delighted in entertaining such a captive audience. Two in particular, LaMacchia and Mattick, took an interest in the inquisitive young Astros executive.

"Pat used to sit around the old guys, listening, observing how they worked," LaMacchia says. "You just knew he wasn't going to stay in an assistant's role his whole career."

LaMacchia and his wife used to have Gillick over for dinner in San Antonio, and the topic of conversation was always the same: baseball. Often Mattick would join the dinner party, prompting Ann LaMacchia to remark that the men were so alike they were almost like triplets. Age was the only difference.

"Both those guys had such great work ethics," Gillick says. "They told me scouting is an opportunity to run your own small business. You have a particular territory you're responsible for, almost like a franchise, and you get the freedom to run your own show and come up with the best way to produce results.

"People in scouting aren't in it for the financial return. The scouting life is not easy. It's tough. But they have a deep love of the game, and they love to scout, sign and see a player develop. That's the reward."

Another reward for Gillick was meeting Doris Sander on a beach in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, in early 1968. Doris, a native of tiny Kettwig, West Germany (pop. 12,000), was a stewardess enjoying an extended layover. Gillick was scouting the Caribbean for the Astros and, as his mother says, "I'm sure he wasn't scouting Doris for a baseball team, but he was scouting her all right."

They were married in November 1968, 10 months after they met.

It was from LaMacchia and Mattick that Gillick learned the joy of gambling--from a scouting perspective.

"They were risk-takers," Gillick says. "They liked to go out on a limb. Now a lot of those risks don't work out, but a lot of them do. You have to evaluate what the rewards are going to be versus what the risk factor is. You weigh that information, and then you act."

Gillick's mother wasn't surprised to see her son gravitate toward the more experienced scouts. He always connected best with older people, beginning with his grandparents, with whom he lived along with his great aunt for much of his youth.

During his college days, when his grandmother was in a nursing home in Long Beach, Gillick befriended one of the other residents, a stroke victim who happened to love baseball. During his summers, Gillick would make the hour drive down to Long Beach, visit with his grandmother and take his new friend to Dodgers games.

"That's just the way Pat is," his mother says. "He could have had young people around him instead, but he often preferred older people. When you look back on it, you realize how many older people he's hired, and they all love him. They could all be his father."

Gillick stayed with the Astros for 10 years, advancing to scouting director and leaving only to accompany Smith when the Yankees hired him away in 1974. The union with a fledgling owner named Steinbrenner was doomed from the start.

Smith and Gillick were all about scouting and player development; Steinbrenner, as soon became apparent, preferred the quick fix and the familiar name. Exasperated, Smith returned to Houston after two seasons in the Big Apple. Gillick stuck it out a little longer, until his dream job finally arrived on Aug. 16, 1976.

The expansion Blue Jays provided a fresh start, a blank canvas and a world of possibilities. Gillick was the first baseball man they hired, and he quickly brought LaMacchia and Mattick with him.

"These last 18 years have been the best years of my life," LaMacchia says, and he could easily be speaking for Gillick as well. Given almost unprecedented freedom to act upon his hunches and stick to his beliefs, Gillick has, by all accounts, delivered the blueprint on how to build a successful expansion franchise.

That's not to say there weren't tough times along the way. Every move wasn't as successful as the Chief Wahoo caper. But once they broke through with an 89-win season under manager Bobby Cox in 1983, the Blue Jays were contenders to stay.

Oh, sure, there were the Blow Jays jokes after the Royals wiped out a 3-1 deficit in the 1985 American League Championship Series, and after the 0-7 final week in 1987. The ensuing years gave rise to the Stand Pat moniker, an idea so pervasive Doris and Kimberley Gillick found themselves clipping out their favorite articles and cartoons on the subject, and posting them on the refrigerator for their target to see.

But then came the Winter Meetings of 1990, when Stand Pat ended a 608-day trade drought with the twin bombshells that brought in Roberto Alomar, Joe Carter and Devon White. It seems like it's been nothing but pennants and parades for the Blue Jays ever since.

Oh, yes, and tears. Gillick can get quite emotional, as he did again this Opening Day while handing out World Series rings in an on-field ceremony at SkyDome.

"Pat's sensitive," Smith says. "He can get emotionally and visibly moved, and not just at negative things either. I've watched events unfold on TV with him, a football game or something, and he lets it show.

"You can see his face wrinkle up as he fights back tears of joy and elation. He gets moved more by factual happenings or events or stories that he hears than by movies or other fictional things. He cares very deeply, and he can put himself in that person's shoes and sense their joy or glee.

"This is not a common trait. People usually don't like to show very much emotion. But Pat can't help it. He's an emotional, compassionate person."

Just ask the turtle.