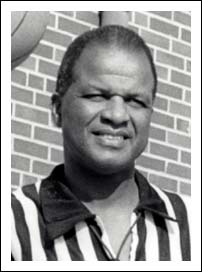

Modie Lee Risher

Born : 06 September, 1928

Died :

17 October, 2016

6'1", 180 lbs

Bats : Right / Throws : Right

Jacksonville Eagles

Charleston Black Socks

Orangeburg Tigers

Columbia All-Stars

Allen University

Lloydminster Meridians

1950 Allen University (Columbia, South Carolina), Batchelor of Science in Physical Education

The accolades keep coming for Modie Risher. In early 2009 the South Carolina House of Representatives marked his 80th birthday with a special resolution noting his considerable achievements as a coach and educator.

Whereas, it is with great pleasure that the members of the South Carolina House of Representatives honor individuals who freely give of their time and resources for the good of others; and

Whereas, Mr. Modie Risher, Sr., of Charleston, an exemplary educator and coach for many years in his community, stands high among their number, much admired for his dedicated work among the youth of the Charleston area; and

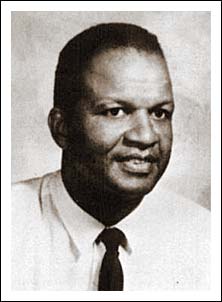

Whereas, born September 6, 1928, Modie Risher graduated in 1946 from Burke High School, where he was a popular and skillful three sport athlete. Continuing his athletic career in college, he played for Allen University while earning his bachelor’s degree, later taking his master’s degree at Columbia University in New York City. In time, he also completed thirty hours’ postgraduate work at The Citadel; and

Whereas, he played professional baseball in the old Negro Baseball League for the Jacksonville Eagles and other teams against such legendary players as Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and Jackie Robinson; and

Whereas, as an educator for thirty three years at Burke High School, his alma mater, he taught health and physical education, as well as creative dance and gymnastics. This perpetually winning coach served as athletic director, department chair, consultant, and school evaluator for the South Carolina State Department of Education, and member of the curriculum guide writing team for Charleston County Schools’ health and physical education teachers; and

Whereas, putting his considerable expertise to good use beyond his own school, he served as an official in the South Carolina High School League, Dixie Professional Football League, and Southern College Conference, among other groups, over a span of thirty two years; and

Whereas, believing a man should be involved in his community, Mr. Risher joined Charleston’s political life as president and executive committeeman for Charleston County Precinct #13 and was very outspoken on issues concerning the African American community. In addition, he volunteered his services to many community organizations such as Jack and Jill of America, and he is president emeritus of the Charleston Chapter of the National Federation of the Blind; and

Whereas, at Morris Brown AME Church, where he receives his spiritual nurture, he has served as junior trustee, director of church recreation, and, from 1994 to 2000, volunteer with the church’s mentoring program at Mitchell Elementary School; and

Whereas, over the years, Coach Risher has received numerous awards and honors for his labors, among them four athletic events and the new Burke High School gymnasium named in his honor, a South Carolina Palmetto Patriot award, and the 2007 Lifetime Achievement Award from the Charleston Metro Sports Council; and

Whereas, on the home front, many years ago he married his beloved DeLaris, the Lord blessing their union with two children, Modie, Jr., and Devonne R. Smalls, as well as two grandchildren, James II and De Ana Smalls; and

Whereas, the House of Representatives also notes that Modie Risher, Sr., celebrated his eightieth birthday on September 6, 2008, and the members are proud to join his family and friends in congratulating this truly gentlemanly South Carolinian on reaching this extraordinary milestone; and

Whereas, the House of Representatives adds further congratulations upon the many expressions of commendation Mr. Risher has received, and still is receiving, for his work as an educator and coach, the fruits of a life filled with service to others. Now, therefore,

Be it resolved by the House of Representatives:

That the members of the South Carolina House of Representatives, by this resolution, recognize and commend Mr. Modie Risher, Sr., of Charleston, for his achievements as an educator and coach, congratulate him on the occasion of his eightieth birthday, and wish him much happiness in the coming years.

In the summer of 2007, Risher was inducted into the Charleston Baseball Hall of Fame.

" ... A standout three-sport athlete at Burke High School, Modie Risher went on to play in a Negro Baseball League for the Jacksonville Eagles, where he faced off against such legends as Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and Jackie Robinson. He also played locally for the Charleston Black Socks and the Orangeburg Tigers. Following his playing career, Risher was a highly successful coach at his alma mater, Burke High, where he coached baseball and football for more than 25 years."

In January, 2006 the Charleston County Council voted, unanimously, to name the Burke High School Gymnasium in honour of Modie, a former three-sport star at Burke and, for decades, the school's football, baseball and basketball coach and athletic director.

Mode and his wife DeLaris were at a special ceremony where the announcement was made. The event was held at the start of the Modie Risher Invitational Basketball Tournament. It was just the latest gesture in his home town to  recognize his accomplishments in the fields of sports, civil rights and community activities. The genial "chatterbox" graced the fields of the Western Canada League as a first baseman, catcher, outfielder for the Lloydminster Meridians in 1957. He had become aware of prairie ball through his old friend, Curly Williams, with whom he had played on Negro teams in South Carolina and Florida. (Just after Christmas, 2005, Modie and DeLaris celebrated their 46th wedding anniversary.)

recognize his accomplishments in the fields of sports, civil rights and community activities. The genial "chatterbox" graced the fields of the Western Canada League as a first baseman, catcher, outfielder for the Lloydminster Meridians in 1957. He had become aware of prairie ball through his old friend, Curly Williams, with whom he had played on Negro teams in South Carolina and Florida. (Just after Christmas, 2005, Modie and DeLaris celebrated their 46th wedding anniversary.)

Risher was a highly regarded backstop in his days in Negro ball :

Risher, catcher. Allen University. Columbia, S.C. who appears to be frontmost in the race to succeed Roy Campanella of the Brooklyn Dodgers, as the top catcher in professional baseball. Risher has been scouted by major and minor league clubs as well as virtually every Negro club. (Atlanta Daily World, May 21, 1950)

In the summer of 2004, the Charleston RiverDogs of the South Atlantic Baseball League Risher was inducted into the RiverDogs Hall of Fame for his service to the African-American community.

" ... Risher, a former three-sport athlete at Burke High School, played professionally in the “Olde Negro” Baseball League. He competed against such legendary players as Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson and Jackie Robinson in the late 1940s and early 1950s in exhibition games.

A coaching career that spanned over 25 years, Risher’s most memorable thrill as a football coach came in 1955 with the defeat of Sterling High School and its talented quarterback, Jesse Jackson (The Reverend Jesse Jackson).

As an educator, Risher earned Teacher of the Year honors, Student Council awards and has had two athletic events named in his honor. Risher has not only served as an athlete and coach, but as an unshakable official, presiding over such football events as the Orange Bowl Classic in Miami, FL.

He was the first African-American to receive the Official of the Year award from the Palmetto Touchdown Club and Dixie Football League in 1971. An active member in Charleston’s political life, Mr. Risher served as President and Executive Committeeman for Charleston County Precinct #13 and was vocal on issues concerning the African-American community. He is also president emeritus of the Charleston Chapter of the National Federation of the Blind." (Charleston RiverDogs)

Modie Risher: Educator keeps his eyes on the prize

by JEFF NICHOLS Originally Published on 4/12/97

A man is born to be a light in the darkness. He's born in the right place. Charleston's struggling West Side, 1928. Southern discomfort.

He's born and he blinks and his father's not around anymore. Now the family's moving again. What's this, the 10th time? Nobody ever tells him why, but the boy figures his family's hard times have something to do with his father not being there.

So little Modie Risher decides to help. He starts thumbing rides after school over to the Charleston Country Club, where the golfers pay him 65 cents to caddy till dark. Loves the look on his tired mother's face when he hands her the money.

On Saturdays, he'll spend the whole day lugging golf bags, bringing home $1.30 for Mamma.

Maybe that - along with the money Virginia Risher makes cleaning houses, maybe that will be enough to keep the family in one place for a while.

But it isn't. This is the South in the '30s. The Depression gets a tighter grip on you here.

So the boy finds solace in dreams. Maybe this Christmas, he'll get the pair of Union No. 5 skates he's always wanted. Maybe this early morning, Mamma will wake him before school and give him three cents so he can head over to Bullwinkle Bakery for a day-old roll and a carton of milk.

Link enough dreams, enough hope, and a boy finds a way to light his own path. And when he discovers sports, the path is so bright, it's almost too hard to look.

When Modie Risher grips his broomstick and wallops that half-rubber ball over the parked cars on Allway Street, there is no Depression. No poverty. No darkness.

Modie plays half-rubber until the day's last light begins to fade. Squinting at the ball as it sinks and rises. He plays football on the street, too. Cracked pavement for AstroTurf.

When you're a natural, it's God's gift that makes you a star. Quarterback at Burke High School. Captain of the basketball team. Honor student. Student body president. Pro baseball standout in the Negro Leagues. And later, a teaching and coaching icon at Burke High School.

But there's something else inside Risher that he can't always express through sports. There's a growing need inside him to question unfairness. To question why he has to play ball in the street. Why there's only one park in the city for black kids and it's too far away.

After graduating from Burke, Risher goes on to become a three-sport college star. He has a reputation for toughness, never more evident than that cloudy afternoon when Modie Risher, the quarterback, faked a handoff, rolled to his left and collided with two defenders who rubbed him into the ground.

Sometimes lives are altered in moments you never see coming.

One of those big defenders, wearing old rusty spikes, will step on Risher's face after the tackle. There are no face masks in the '40s.

He'll bury his spike just under Risher's left eye. No backing down

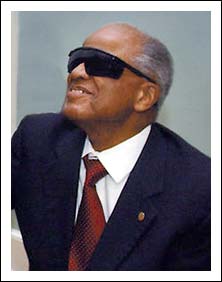

Modie Risher, now the retired educator, was driving down I- one day in 1987 when the words on the big green signs overhead began to fade in and out.

It was a little like back when he was a teacher at Burke and the words he'd just written on the blackboard would get blurry now and then.

``Back then, I'd just get a little closer to the board,'' Risher says. ``But that day on the interstate, I knew something was really wrong.''

After all these years, the light was beginning to fade. Risher was going blind.

That rusty spike left him with more than a scar. It left him with nerve damage. Optic degeneration, the New York retinal specialist said, a slow 40-year fade.

``I've only got a tunnel of light left and it's growing smaller every day,'' says Risher, recently elected president of the Charleston chapter of the National Federation of the Blind of South Carolina.

Facing the struggle

Living with the fade leaves him dependent on his wife, DeLaris, to take him to ballgames at Burke. The fade has him learning to read Braille, learning to listen for idling cars at the street corner, learning about the struggles blind folks face.

He couldn't believe it when he heard about the blind man in Ohio who got a ticket for jaywalking, couldn't believe it when he found out how many blind folks each year are hit by cars rolling through stop signs.

More stories of injustice for a man who's lived through his share.

It was Risher who, as sports coordinator for the city parks department, could have gone to jail when he defied city officials and turned on the lights at Harmon Field so the softball teams could practice at night. He hadn't played all those games in the street only to see black teams in the park forced to pay $45 per evening for lighting.

When the teams refused to pay the fee, which wasn't levied at other city parks, the city had the lights turned off.

Risher turned them back on. Then he got City Council to abolish the fee. ``

Delivered a Gettysburg Address that night,'' he says.

It was Modie Risher who had an answer in 1971 for the white basketball coaches who said Burke would no longer be invited to play in a city basketball tournament.

He started his own, the Burke Invitational. Invited inner-city teams, and the people packed the gym. Renamed the Modie Risher Classic in 1978, his tournament was a Charleston basketball showcase until it ended in 1992 when Burke joined another city tournament.

``One of the hardest things a man can do is to try to bring about change,'' Risher says. ``I've tried to do some of that, but I did it with the children in mind.''

Now 68, Modie Lee Risher stands up for the blind, those who live and hope in the tunnels of faded light.

``You'd be surprised at the obstacles some of us face,'' he says.

Diamond dreams

Segregation. There's an obstacle. It's the mid-'40s and Risher must climb back on the bus with his sweaty, smelly team mates on the Lakeland, Fla., baseball team because the ball park showers are off-limits to blacks.

This is Negro League baseball. Where all those games of half-rubber have taken him. The buzz is that a player will soon be chosen from the talent-rich Negro Leagues to break Major League Baseball's color barrier.

``You heard about that and it seemed like this dream you could almost believe in, but then you would wake up again,'' he says. ``But all of us were hoping. That's all we had was hope.''

Hope will help Risher ignore the racial slurs he hears as he's getting off the bus. Didn't they want a black man who could control his temper?

It will help him make that long trip to Baltimore or New York or Pittsburgh on an old bus that the players have to fix when it inevitably breaks down.

Urinating behind trees because most of the bathrooms along the way are for whites only.

Seventeen-year-old Modie Risher would sit there on that bus, his new world rushing past his window, hurtling him to the next game where a major league scout could be waiting to choose him. The game is his light, his talent an offering.

``It was tough back then,'' he says. ``There wasn't any use complaining at that time. You just had to love the game to play baseball in the Negro Leagues.''

Risher plays against legendary pitcher Satchel Paige and slugger Josh Gibson. He plays against Jackie Robinson, who will later make history when the Brooklyn Dodgers make him the first black player in the majors.

He earns enough to send most of his $500 a month paycheck home. Would've taken him about three years to make that much lugging golf bags back in Charleston.

Risher had received an athletic scholarship to Benedict College in Columbia, but the chance to play baseball with top-notch talent was too good to let slip away.

He keeps hoping, just as he had hoped for the roller skates, that his talent will lead to a call from a major league scout. But the call, like the skates, never comes. Sometimes the light fades too soon.

And sometimes your mamma steps in.

``The coach at Benedict started calling my mamma and asking about when I was going to give up baseball and go to college,'' Risher says. ``She was already wanting to know how in the world I was able to make so much money playing baseball. She thought I must have been up to something else so she told me to come home and go to college.''

Risher listened to his mamma, turning down an offer in 1946 to play with the lofty Newark Eagles of the Negro Leagues, which would have meant playing in front of major league scouts nearly every night.

Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier the very next year. Risher headed off to college instead. But just to one-up the Benedict coach who called his mamma, he accepted a full scholarship offer from Allen University in Columbia.

Across the street from Benedict.

Tough love

A man born to shed this much light will go where he knows there's certain darkness. He goes home to teach after college, home to Burke High in the old inner-city neighborhood, and the kids who need a burning match in their lives.

He inherits the football team from coach Joseph Moore in 1955 and molds it into a power. Preaches his gospel of discipline. ``I'll say it once and we'll do it a thousand times,'' he barks over and over.

Risher hates complication, hates fancy. He wants poundcake football. Here's a couple of running plays, here's a couple of pass plays. That's it, no icing.

Now he's running his players after practice until they're on their knees crawling the last laps. But they'll finish. Risher will stand there until the last kid does. His team is small; they can't afford not to be in shape. But that's not the main reason Risher makes them run.

``After my practices, I never had to worry about where my kids were at night,'' he says. ``I knew they'd be too tired to leave the house.''

He knows where they are on Friday afternoons before games, too. In the Burke gym. Lying there on the floor, thinking about the game. Waiting on that lone bowl of soup at 5 p.m. ``I wanted them mean, lean and hungry,'' Risher says.

And disciplined. If a kid jumps offsides during practice, he'll bend over so a teammate can paddle him on the behind. One kids gets so used to it, he bends over for a paddling in the middle of a game.

``So much of what Modie gave these kids were two things they weren't getting at home and that was discipline and love,'' says Burke athletic director Earl Brown, a former student of Risher's and a lifelong friend. ``He knew when to be your father and when to be your friend.''

The running and the soup and the discipline leads to a 9-0 record and a state championship in 1955. It leads to Risher's team taking a bus to Greenville to play Sterling High, led by a quarterback named Jesse Jackson. ``I'll always remember that team getting off the bus in their coats and ties,'' Jackson will say years later on a visit to Charleston.

The discipline leads to Modie Risher benching Leroy Wine, the captain of his '55 team, when Wine shows up in Greenville without his stockings.

``He wanted to borrow a pair from one of his teammates,'' Risher says. ``I told him it doesn't work like that. Even when you're captain.''

Even without Wine, the Bulldogs knock off Jackson and Sterling High 8-0 on the way to the only state football title in Burke history.

Risher will lead the Bulldogs to a 98-16 record in his 13-year coaching career, his last loss coming on a rainy night in Spartanburg in the 1968 state title matchup with Carver High.

The night ol' Leroy ``June Bug'' Connors breaks the head off the runners-up trophy after the game and hands it to the referee. A dejected June Bug and his teammates had three touchdowns called back on penalties.

You just knew June Bug was in for it that night. Had to wince as Modie Risher, the burning light of discipline, walked slowly over toward him, surely about to teach the kid a lesson he'd never forget.

Sometimes lives are altered in moments you never see coming.

``It's going to be OK, son,'' Risher said, putting his arm around June Bug, the two of them standing there in the rain and the darkness. ``It's going to be OK.''

Mr. Everything

A man born to shed this much light will be father to an entire school. He coaches for 25 years, chairs the Burke physical education department for 23 years and serves as athletic director for 15 years. He coaches the basketball, baseball and track teams at Burke, winning eight Lower State titles.

When he's not coaching, he finds time to train the cheerleaders and majorettes, for crying out loud. He coordinates the halftime shows and when he retires from Burke in 1983 - 33 years after the day he came back - he serves as the Voice of the Bulldogs at football games, giving it up only when that spike in the face of so many years ago finally catches up with him.

He teaches physical education, health education, creative dance and gymnastics at Burke, all things he learned both at Allen and at Columbia University where he earned a master's degree in physical education.

Risher even choreographs the locally famous Burke High School Coronation Ball.

His nickname is ``Everything.''

``Modie simply was Burke High School,'' says former Burke principal Wilhelm Meriwether. ``He was a father figure to so many kids. You couldn't go to school at Burke back then and not cross his path.''

Should have seen him during those R&R sessions (Rappin' with Risher), taking time out to shut up for a while and let the kids do the talking. See him blink back the tears one afternoon when a student talks about the father she longs to see again. See Risher touch her gently on the shoulder the way he touched June Bug that night, wishing his whole life that a touch could somehow absorb despair.

``Whether you're talking about then or now, kids just need somebody to listen to them, somebody to show them they care,'' says Risher, who, with DeLaris, reared two children of his own. ``When a kid was down or when I wanted to show I was proud, I touched them.''

Claflin College will try to lure Modie away in '67. The Orangeburg school offers him the head basketball coach's job and a teaching position. He thinks about it hard for a month. But this father won't walk away.

He'll save the letter from Claflin in a scrapbook, but he won't leave the kids of ``separate but equal'' Burke alone with their tiny gym and run-down football stadium.

The Claflin offer was so much like back when Risher first started teaching at Burke. Back when he was working on his master's degree at Columbia University during the summer. While living with his sister in Brooklyn, he got a job at Domino's Sugar Refinery, working there when he wasn't in class.

He worked on the second floor in the automation department, a position at Domino's no black man had ever attained. The Jackie Robinson of Domino's. So good at his job that Domino's tried to get him to stay when he finished Columbia. Offered him more money than he would ever make as a teacher.

``But Mr. Meriwether called and said the kids needed me and that's all it took,'' Risher says. ``I knew Burke would give me the opportunity to touch lives.''

Extra credit

To touch this many lives, a man decides to reach kids before he sees them in high school. So in 1961, Risher begins a 22-year career with the city recreation department. Gets his hands on the clay while it's still wet.

Races over to Harmon Field after a day of teaching and coaching at Burke to show a pint-size quarterback how to throw a spiral. Stays up late at night organizing teams and schedules. He moves up from special events director to assistant sports coordinator to sports coordinator.

``Modie's just one of the most devoted men you'll ever hope to know, someone with a love for young people that is unsurpassed,'' says Oscar Feldham, who worked with Risher at the recreation department.

All the while, Risher somehow finds time to officiate high school and college basketball games, yet another way to be closer to young people.

The Palmetto Touchdown Club of Charleston creates a new award in 1971 to honor the Official of the Year. The first recipient is Modie Risher. In 1996, he's elected to the S.C. Basketball Officials' Hall of Fame.

Shine on

Modie Risher claps his hands quickly and the sound turns on a light in his Ashley Avenue home, just up the street from Burke. A faint light is all he can see now. He uses it to navigate around the house. DeLaris drives him to ball games, or to National Federation of the Blind meetings, or to visit their grown children.

``She's what every blind person needs,'' Risher says, ``someone who cares.''

Risher smiles and rubs his sore knees - they still hurt from his football days - while he tells you about the Federation of the Blind state convention coming to Charleston in October. About the Charleston chapter's desperate need for a van.

About coping with blindness.

``I still do the things I've always done,'' Risher says. ``I even take out the trash at night. Keep that one outside light on and I've got my beacon back to the house. But, you know, one day I guess the lights are going to go out completely for me.''

But how can that be? How can the light ever fade when a man touches this many lives? Maybe it can't fade after all with the sound of grateful cheers all around.

The sound of a city clapping.

Risher adds another honor to his string

by PATRICIA B. JONES

Originally Published on 3/30/95

To anyone who knows Modie Risher, it would appear that he's received just about every sports honor on the local, state and even national level.

Risher, a retired coach, athletic director and chairman of the recreation and physical education department at Burke High School, has touched many young lives through his love of sports.

Earlier this month, Risher added another accolade to his plaque-covered walls. He was inducted into the Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference Officials Association Hall of Fame in Baltimore for basketball and baseball.

``This award tops it all,'' Risher said. ``It's a great honor to be mentioned in the company of NFL officials like Johnny Grier,'' he said.

The Mid-Eastern Athletic Officials was formed in 1970 in order to establish a new conference based along the Atlantic Coast that would organize and supervise an intercollegiate athletic program among a compact group of educational institutions.

During the early days of the conference, Risher said, officials were not paid handsomely, but money wasn't an issue.

``It was the camaraderie and the dedication... just working with the kids is what kept us going,'' he said.

``Most people get awards or recognition after they're dead and so far, I've been fortunate to smell my flowers while I'm still living,'' Risher said.

Risher, a Burke alumnus, graduated from Allen University in Columbia in 1950 with a degree in physical education. He obtained his master's degree at Columbia University in New York.

In 1971, he was the first recipient to be named Official of the Year by the Palmetto Touchdown Club of Charleston and the Dixie Football League.

In 1977, he retired from coaching at Burke, but continued in a teaching capacity until 1983. He also worked for 22 years for the city's recreation department, where he served as a recreational supervisor and sports coordinator.

In 1978, the Burke High School Invitational Basketball Tournament - which was started by Risher when he was athletic director and coach - was renamed the Modie Risher (Holiday) Classic.

Nowadays, Risher can be found in the classrooms of Mitchell Elementary School, where he volunteers his time in the school's mentor program. He also plays an active role in the newly formed Burke Community Outreach Committee.

``There are so many things that Burke needs and as concerned citizens and parents, we have to come together to give assistance in any way we can,'' Risher said.

Risher said maintenance of the buildings, and a lack of facilities at the school, such as its own football field or swimming pool, need to be looked into.

``We still have leaks in some of the buildings and Burke is the only school that doesn't have its own football field; and now they have to share Stoney Field with the Charleston Battery Soccer Team,'' he said.

He feels that Burke needs more recreational sports that will last a lifetime, such as swimming and track.