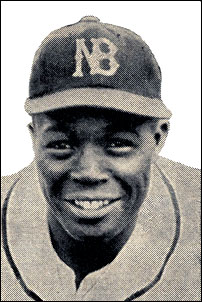

Willie "Curly/Curley" Williams

Batted Left, Threw Right

5' 10", 175 lbs.

Born :

May 25, 1925 in Holly Hill, South Carolina

Died : August 23, 2011, Sarasota, Florida

1946 Columbia All-Stars

1947-1948 Orangeburg Tigers

1948 Newark Eagles, Negro National League

1949-1950 Houston Eagles

1951 New Orleans Eagles

1951 Colorado Springs, Western League (A)

1952 Toledo, American Association (AAA)

1952 Scranton Eastern League (A)

1953 San Antonio, Texas League (A)

1953 Carman Cardinals, ManDak League

1954 Birmingham Barons, Negro American League

1955-1963

Lloydminster Meridians/GreenCaps

Mr. Baseball in Lloydminster.

For nearly a decade not only was he one of the league's best players, but one of the most popular. The "aw-shucks" demeanor and wide smile made him a favourite throughout the league.

"Curly Williams was one of the finest gentlemen that I ever met. (He) was always helping the kids. We'd get these young college boys and Curly was in there talking to them, showing them how to do it. Curly was a Triple-A ball player, and he stayed with us as long as our league lasted." (Slim Thorpe, in 75 Years of Sport & Culture in Lloydminster)

He came to the prairies after a career in the Negro Leagues and a stint in pro ball with the Chicago White Sox organization where he reached the Triple-A level with Toledo (in his first game with the club Curly won three steak dinners and a savings bond for a triple which knocked in the first runs of the season). (Williams seemed to have the knack to made a good, first impression. When signed by the White Sox and assigned to Colorado Springs he belted a two-run homer in the bottom the ninth inning for a season-opening victory.)

As a teenager Williams, and long-time friend Modie Risher, began playing with Negro teams in Charleston, Lakeland, Jacksonville and Orangeburg in the 40s.

As a teenager Williams, and long-time friend Modie Risher, began playing with Negro teams in Charleston, Lakeland, Jacksonville and Orangeburg in the 40s.

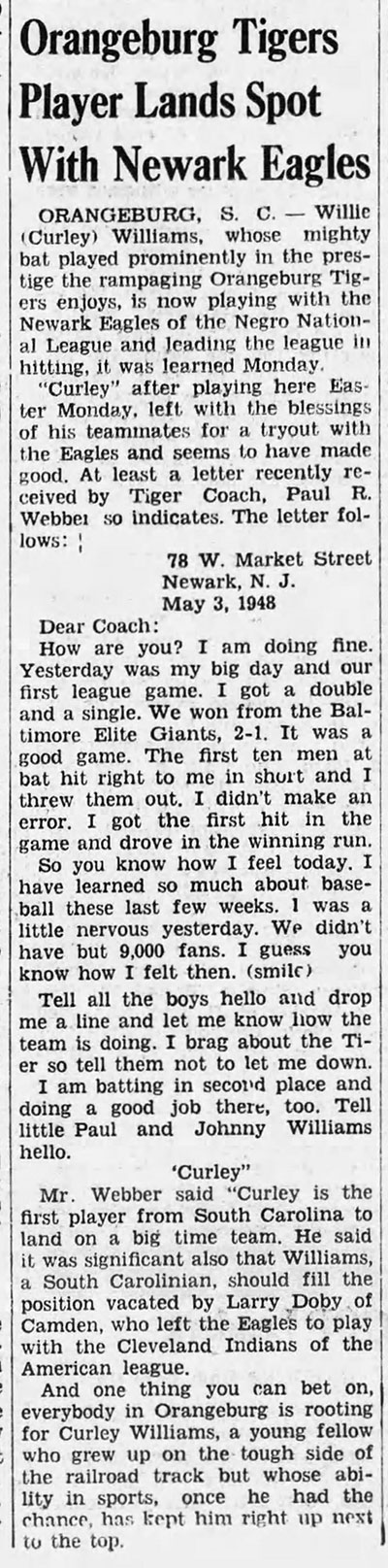

"Curley Williams, promising Negro baseball players who starred at shortstop with the Columbia All-Stars and Orangeburg Tigers, is now making a go of it with Newark in the Negro National league. In the opener recently against Baltimore he got a double and single in five times up to figure prominently in his club's 2-1 win. He is considered a major league prospect by scouts, who watched him last year in Columbia." [In the Press Box with Jake Penland, The State, May 11, 1948]

He'd win a spot on one of the "major" Negro League teams in 1948. A letter from Williams was published in the May 21st edition of the Alabama Tribune.

Williams, then a shortstop, was a member of the Newark Eagles (and its successors) from 1948 to 1951 and was selected to play in the 1950 East-West All-Star game.

He also played winter ball in the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico. In late 1949 in Puerto Rico, Williams, on a homer spree, attracted the attention of the Caribbean scout for the New York Giants. Then after the 1950 All-Star game the Chicago White Sox came calling.

Left - Williams played at least two winters, 1949-50 and 1950-51 with Mayaguez of the Puerto Rican League. Right - with the Newark/Houston Eagles.

Below left - Williams in Triple-A with Toledo in 1952. The caption of the photo in the Chicago Defender read "Willie Williams, formerly with the New Orleans Eagles, is making good with the Toledo Mudhens in the American Association". (June 7, 1952)

In the pro ranks, Williams reached Triple A, but with a lack of opportunity for "coloured" players, he reached across the border for a chance to play in Canada.

In the pro ranks, Williams reached Triple A, but with a lack of opportunity for "coloured" players, he reached across the border for a chance to play in Canada.

"It was awful. I cried so much when I was in professional baseball, I tell you. (In Canada) we were treated so well up there that's why I stayed up there so long ... We had so much fun there and everybody was accepted, you know, didn't have problems going any place we wanted to eat. Just wonderful people. May not have made a whole lot of money but people were excited and they enjoyed you and would invite you to their homes."

He suited up with the Carman Cardinals of the ManDak League in 1953 then, after seasons in the Dominican and back in the Negro League, became a fixture on the prairies.

In his first season in Lloydminster, he hit .280 and, as a third baseman, led the league in fielding. The following year, he was the team's leading hitter with a .314 average, 7 homers and 45 RBI. Again, he'd lead the league in fielding, this time at shortstop.

He was a perennial all-star who also took a turn as manager of the club. In his first full month as manager in 1961, Williams led the Meridians to 25 wins in 32 games, including tournament victories in Lacombe and Lethbridge. Curly loved Lacombe. In the 1960 tournament he reached base 14 times in 15 appearances. In the 1961 event, Williams had three hits and scored twice in the semi-final match as a warm-up for the final in which in homered, tripled and doubled, drove in four runs and scored a pair.

He was a perennial all-star who also took a turn as manager of the club. In his first full month as manager in 1961, Williams led the Meridians to 25 wins in 32 games, including tournament victories in Lacombe and Lethbridge. Curly loved Lacombe. In the 1960 tournament he reached base 14 times in 15 appearances. In the 1961 event, Williams had three hits and scored twice in the semi-final match as a warm-up for the final in which in homered, tripled and doubled, drove in four runs and scored a pair.

After the collapse of the Western Canada League at the end of the 1961 season, Williams returned to Lloydminster to head up the city's entry, the Green Caps, in the Northern Saskatchewan League. Those would be the final two seasons of his 20-year baseball career. Curly retired after the 1963 season. Fittingly, he went out with a blast -- a .391 average.

"Such a nice man, beautiful, just beautiful", said Risher "too nice sometimes. I used to get on him about it, telling him you can't be the saviour for everybody".

In 1997, the Sarasota, Florida Council declared "Curly Williams Day" in honour of his efforts to raise funds (through the Curly Williams Foundation) to provide college scholarships for needy students.

Team League Pos AB H D T HR RBI SB AVE

Lakeland Tigers

Jacksonville Eagles

Orangeburg Tigers

Columbia All-Stars

1948 Newark Eagles NNL ss

1949 Houston Eagles NAL 210 61 .290

1949 Mayaguez PR

1950 Houston Eagles NAL ss 250 73 15 5 8 32 2 .292

1950 Mayaguez PR

1951 Colorado Springs WEST ss 64 19 2 1 4 19 0 .297

1951 New Orleans Eagles NAL ss 262 92 - - 11 62 - .351

1952 Toledo-Charleston AA 128 20 3 2 2 14 0 .234

1952 Scranton EAST ss/2b 228 61 8 4 5 30 5 .268

1953 San Antonio

TEX ss

1953 Carman ManDak 199 57 15 1 12 40 4 .286

1953 Licey DMSL 37 4 - - 0 3 - .108

1954 Birmingham NAL ss/of 241 68 17 2 12 58 6 .282

1955 Lloydminster WCBL 3b 211 59 13 4 5 33 3 .280

1956 Lloydminster WCBL 3b/ss 204 64 12 3 7 45 7 .314

1957 Lloydminster WCBL 3b 242 83 14 3 15 55 4 .343

1958 Lloyd-NB WCBL 3b 179 59 11 5 5 41 2 .330

1959 Lloyd-NB WCBL 3b 215 56 11 3 11 59 1 .260

1960 Lloydminster WCBL 3b 233 72 19 2 4 40 3 .309

1961 Lloydminster WCBL n/a

1962 Lloydminster NSBL n/a

1963 Lloydminster NSBL * 69 27 4 1 3 16 2 .391

* Incomplete

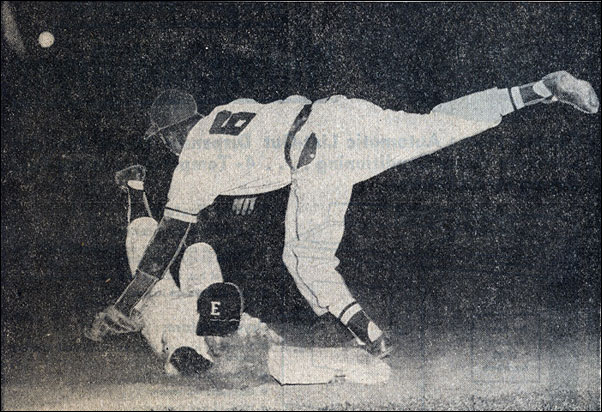

June 14, 1958 Curly Williams in action at third base for Lloydminster. That`s Roger Tomlinson

making the head first slide.

Published in the Sarasota, Florida, Herald-Tribune August 25, 2011

Baseball pioneer Williams dies in Sarasota

By Billy Cox

SARASOTA - Willie "Curley" Williams, one of baseball's quintessential journeymen who started his career in the Negro Leagues, died early Tuesday morning under Hospice care at 86, following complications from a stroke.

SARASOTA - Willie "Curley" Williams, one of baseball's quintessential journeymen who started his career in the Negro Leagues, died early Tuesday morning under Hospice care at 86, following complications from a stroke.

The former power-hitting shortstop and third baseman made it as far as the Chicago White Sox AAA team, but spent most of his 15-year professional baseball career strapping on cleats in locales as disparate as Canada and Puerto Rico. He spent the last 47 years of his life in Sarasota.

"Newark, Scranton, Houston, New Orleans, Birmingham, Toledo, Colorado Springs, Jacksonville — this guy went everywhere," says longtime friend, Houston rehab therapist Dr. Layton Revel. "He was the epitome of what a baseball player was like in the '50s.

"And he posted big numbers everywhere he played. I mean, in '63, he's 40 years old and he's hitting close to .400."

The 1963 season was his final year as a pro, when Williams was a player-manager with Lloydminster of the Northern Saskatchewan Baseball League. He batted .391.

Williams moved to Sarasota the same year, where he worked as a pathology assistant in the Sarasota County medical examiner's office until his retirement in 1990. His Willie "Curley" Williams Foundation would later grant college scholarships to underprivileged students, and the Sarasota City Council proclaimed a "Curley Williams Day" in 1997.

Annette Williams, his wife of 22 years, said he got his nickname from "wearing processed hair like Nat King Cole." She said he followed baseball, particularly the Atlanta Braves and the Tampa Bay Rays, until the end.

Johnny "Lefty" Washington, a Williams teammate with the Houston Eagles in the late 1940s, fondly remembered his buddy — who also played third base — but not solely for his athletic skills.

"Oh, he was a good hitter, a line-drive hitter and a place-hitter. And he was smart," Washington, 81, recalled from his home in Chicago.

"But he also tried to talk us up to the minor league teams. Curley knew a lot of people and he got quite a few players up there."

Williams once snickered at one of Hollywood's most famous attempts to revisit the era of segregated baseball, in the 1976 Richard Pryor comedy, "Bingo Long and the Traveling All-Stars."

"There wasn't any clowning around on ratty buses," Williams said. "We were there to play serious baseball, and we rode in a brand-new Greyhound bus."

Chicago baseball historian Gary Crawford, a friend of Williams, says roughly 200 veterans of the Negro Leagues are still alive. Crawford posts all those statistics, including those of Williams, online at attheplate.com

"Curley was a real stand-up guy," Crawford said. "He was a caring person and he really put his money where his mouth is."

Visitation for Williams is 5 to 7 p.m. Sunday at Jones Funeral Home in Sarasota. Services will be 11 a.m. Monday at Bethlehem Baptist Church in Sarasota.

Survivors also include daughter Jaquelyn McNeil of Bradenton; son Todd Bryant of St. Petersburg; brother LaSalle of Orangeburg, S.C.; stepdaughter Paula Farlin of Sarasota; and five grandchildren.

(Adapted from Legends of the Negro Leagues)

Willie "Curly" Williams was born in Orangeburg, SC on May 25, 1925, the youngest of seven children. His father had passed away when he was only six months old. The family remained in Orangeburg, where Willie attended school and played football and baseball. While still a teenager in high school he had won a spot on the local baseball team, the Orangeburg Tigers which would challenge Negro League teams which barnstormed through the area. It was as a member of the Tigers that the Newark Eagles discovered the young shortstop. Williams joined the Eagles in the spring of 1945 and remained with the club for four seasons in Newark and, when the team shifted to Houston, another two summers. The 1946 team won the Negro National League championship. Williams batted against some of the greatest pitchers in baseball history - Satchel Paige and Don Newcombe, as two examples. In winter ball, Williams played both in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. One of his most memorable periods came in winter ball play in Puerto Rico when, in a six day period, he crushed seven home runs.

Willie "Curly" Williams was born in Orangeburg, SC on May 25, 1925, the youngest of seven children. His father had passed away when he was only six months old. The family remained in Orangeburg, where Willie attended school and played football and baseball. While still a teenager in high school he had won a spot on the local baseball team, the Orangeburg Tigers which would challenge Negro League teams which barnstormed through the area. It was as a member of the Tigers that the Newark Eagles discovered the young shortstop. Williams joined the Eagles in the spring of 1945 and remained with the club for four seasons in Newark and, when the team shifted to Houston, another two summers. The 1946 team won the Negro National League championship. Williams batted against some of the greatest pitchers in baseball history - Satchel Paige and Don Newcombe, as two examples. In winter ball, Williams played both in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. One of his most memorable periods came in winter ball play in Puerto Rico when, in a six day period, he crushed seven home runs.

In 1950 he was selected to play in the annual East-West All-Star game in Comiskey Park, Chicago after which the Chicago White Sox signed him to a pro contract. He took his game to the Triple-A level in the White Sox organization which, however, already had a young Chico Carrasquel at shortstop with Luis Aparicio soon to replace him. Noting the limited opportunities in pro ball, especially as he reached his late 20s, William headed north and joined the Carman, Manitoba, Cardinals and host of other former Negro League players in the ManDak League. He had a strong season, .286, 12 homers and 40 runs batted in over just 199 at bats. He was lured back to the Negro Leagues in 1954 when he was one of the stalwarts of the Birmingham Black Barons. The following season, he'd begin a nine-year hitch with Lloydminster of the Western Canada and Northern Saskatchewan Baseball leagues. Not only was he one of the most popular players, Williams continued to perform at a high level and also took up managerial duties for the final few seasons of his career. He retired from baseball after the 1963 season. Williams put in twenty-seven years with the Sarasota Coroners office before he retired in 1990.

ROBINSON NOT THE ONLY BARRIER BREAKER

PLAYER REMEMBERS HISTORIC DAYS

(Sarasota Herald Tribute 05-09-97)

(Photo not yet available) STAFF PHOTO/MATT BERNHARDT

Willie ``Curly'' Williams, a former member of the Negro League, sports a Newark Eagles cap and a Negro League T-shirt when he appears in Punta Gorda on Thursday to speak to a group of black community leaders. Behind him is a poster he brought along covered with photos of great black baseball players of his day.

Black baseball players all broke color lines

By Thomas Becnel STAFF WRITER

Willie ``Curley'' Williams knew the great Jackie Robinson, played ball with him, learned from him.

And now, in the much-celebrated 50th anniversary year of Robinson's breaking the barrier in Major League Baseball, he's being honored like him, too.

Williams joined several Negro League veterans at a Florida Marlins game last month, and he spoke Thursday in Punta Gorda to a group of black community leaders who are establishing a scholarship in his name.

The 72-year-old Sarasota resident never made it to the majors, but he did play AAA ball and was one of the first blacks to play in the old Texas League. He was a power-hitting shortstop with the Newark Eagles when they won the 1946 Negro League championship, defeating Josh Gibson and the heralded Homestead Grays.

In the off-season, Williams played against the Jackie Robinson All-Stars on barnstorming tours throughout the country. Even then, Robinson was a hero, a larger-than-life figure.

``We'd all go to the hotel with him after the games,'' Williams said. ``He'd sit around, play pinochle and talk baseball with all the players gathered around him. He'd talk to you about what to expect and how to carry yourself, because he'd been through all the crap we were going through.''

Like so many black baseball pioneers, Williams had to eat at different restaurants and stay at different hotels than his white teammates. He also stuck it out - again, like so many others - and played professional baseball until he retired to Sarasota with his wife, Annette, in 1963. He worked for the Sarasota County coroner's office until he retired again in 1990.

The newly formed Citizens for Youth Achievement recognized Williams' career Thursday in Punta Gorda. The Rev. Carl Brooks of Macedonia Baptist Church described him as one of a generation of black baseball pioneers.

``As we all know, Jackie Robinson got most of the attention, but there were other men who opened the door for him,'' Brooks said. ``They were all role models.'

Gehodiest Cossey also praised Williams, and then apologized for what he might have done to him as a batboy for the old East Chicago Giants.

``We tried to short the visiting team in everything,'' Cossey said, laughing, ``because we wanted our guys to win.''

Williams wore a Newark Eagles cap on Thursday, along with a Negro Leagues commemorative T-shirt. He brought along a poster with photos of the great black players of his day.

There was Hall-of-Fame Willie Mays: ``People always talk about his famous World Series catch, but that was nothing. That was a routine play for him when he was younger, playing in the minor leagues.''

Legendary pitcher Satchel Paige: ``He was awesome, even as an old man. I couldn't hit him.''

Famed catcher Roy Campanella: ``There was never a dull moment around him. We called him Mr. Happy-Go-Lucky.''

Country-western singer Charley Pride: ``He was a decent pitcher. Later on he tried to play outfield.''

Williams remembers Negro baseball when it was the big time, the big leagues of the black community. He thinks it's been misrepresented in movies like ``Bingo Long and the Traveling All-Stars.''

``There wasn't any clowning around or traveling on ratty buses,'' he said. ``We were there to play serious baseball, and we rode in a brand-new Greyhound bus.

``You wouldn't believe it today, but sometimes we outdrew the Major Leagues. We'd play the House of David team in Brooklyn and we'd draw 20,000 people, and the Dodgers would draw 15,000.''

Today Williams' hair is gray at the temples and thin on top. When he broke in with Newark, though, he soon picked up the nickname Curley.

``Back then,'' he said, smiling, ``young guys used to wear processed hair. The guys were just teasing me about that, saying no one should ever ask how I got that name.''

In the 1950s, Williams played in the Chicago White Sox organization, but that team already had a shortstop, Hall of Famer Luis Aparicio. So the Orangeburg, S.C., native bounced around the country - Toledo, San Antonio, even Saskatchewan - playing in different minor leagues.

In the winter, Williams played in Cuba and Puerto Rico. There he had a career highlight, hitting seven home runs in six games.

Playing year-round, he earned a good living for his family and put his children through school. Today, his son works for a professional cleaning company in Clearwater and his daughter is a high school principal in South Carolina.

This year, especially, Williams is enjoying the attention paid to Robinson and other blacks who began playing in formerly white baseball leagues. There have been ceremonies at the Negro Leagues' Baseball Museum in Kansas City, and a half-dozen other sites.

``A group of us in Florida - about 10 in Miami, and more in the Tampa area - went to a Marlins game last month,'' he said. ``We signed autographs for about two hours, and one of our guys threw out the first pitch.

``I got a chance to play with some of the greatest black baseball players ever, and I'm honored to be a member of that group.''

(THE SARASOTA HERALD-TRIBUNE May 29, 1998)

WILLIAMS RECALLS HIS BIT OF HISTORY

By Brian Ettkin STAFF WRITER

The media attention highlighting the 50th anniversary of Jackie Robinson boldly playing where no black man had ever gone was all-pervasive last year, and yet the name still draws blank stares from those who should know better.

Jackie Robinson? Negro Leagues?

Both were revelations to a Chicago White Sox rookie whom Willie ``Curley'' Williams talked to during spring training last year at Ed Smith Stadium.

``You mean you all had a league?'' the minor-leaguer asked Williams, a former Negro League player who moved to Sarasota after his playing career ended in 1963.

They had a league, a league of their own, though not necessarily of their choosing. Robinson, Larry Doby and the other black players who followed changed that, opening Major League Baseball's guarded birch-white doors. But to the chagrin of Williams and others, many of today's players skipped right over that important chapter of the game's history.

``It does bother me, especially when a black player can't remember Jackie Robinson,'' said Williams, who will be at the Cooper Street Recreation Center in Punta Gorda at 7 tonight for a banquet in which Williams' foundation will present three $500 scholarships to Charlotte County students. Three Sarasota County students will be presented scholarships on Friday, June 5.

``It's awful,'' added Williams, 74. ``They were such great players: Robinson, Josh Gibson, (Satchel) Paige. I don't understand why they don't know about it.''

Williams was a power-hitting shortstop himself who signed a contract with the Chicago White Sox in 1949 and made it as high as Triple-A. But after a player whom Williams felt he had outperformed received most of the playing time in spring training for two straight years, Williams quit the White Sox and finished the season playing in the Dominican Republic.

``I had a good season,'' said Williams, who worked for the Sarasota County coroner's office for 27 years until he retired in 1990. ``A white player had a season not nearly as good as mine but played in all the games during spring training. I didn't get to play in any exhibitions, and I asked (manager Paul Richards) . . . I was so mad. The manager said there's nothing he could do about it.''

Upon returning to the White Sox the following year, the organization tried to send Williams to what was then Class C ball, but Williams refused to join that rookie league. ``It would have been embarrassing,'' he said.

He eventually accepted an assignment to the Double-A Texas League before leaving the White Sox and ending his playing career in Canada, never making the majors.

``I think about it some time,'' said Williams, who played for the Newark Eagles when they won the 1946 Negro League championship, beating Gibson and the Homestead Grays. ``I think the age factor had something to do with it. . . . But I don't feel mad about it.''

Too much time has passed, and Williams mostly recalls all of the good times on trips such as last year's to Miami where a group of former Negro League players were honored before a Marlins game. They will never forget.

(Sarasota Herald Tribune, November 6, 1997)

VEGAS-STYLE CRUISE BENEFITS

SCHOLARSHIP FUND

Approximately 150 people attended a Vegas-N-Venice fund-raising excursion on Oct. 22 to benefit the Willie ``Curley'' Williams Foundation, which provides college scholarships for students in need.

Emcee Carlos Suarez introduced Roy Gavin, president of the foundation, and Sarasota Vice Mayor the Rev. Jerome Dupree. He presented ``Curley'' with a proclamation from the Sarasota City Council designating this day as ``Curley Williams Day.'' Williams accepted and thanked the council for the honor and recognized his wife, Annette, for her support. Foundation Board Member Standford Harper and Punta Gorda City Councilwoman Dawn MacGibbon spoke briefly. The Rev. Gary Suber gave the invocation. The program was followed by a buffet dinner before boarding the boat for a choice of entertainment. As the evening wound down, the guests disembarked and Gehodiest Cossey made sure everyone got on their busses and headed for home. On this evening, everyone was a winner.