Even by the 1950's, Cubans were no strangers to the Canadian prairies. The Indian Head Rockets and the Florida Cubans were two squads which featured players from Cuba.

Even by the 1950's, Cubans were no strangers to the Canadian prairies. The Indian Head Rockets and the Florida Cubans were two squads which featured players from Cuba.

The Brandon Greys of the Manitoba Senior League were among the earliest to begin importing Cuban players. In 1948 the Greys had Rafe Cabrera (identified in the local paper as "Ralph Calberro") and Bus Quinn (who played under his real name -- Armando Vasquez -- in later years).

The 1951 edition of the Greys featured at least a half dozen Cubans, including teenage pitchers Amancio Ferro and Armando Suarez. Pedro Naranjo was a key member of the pitching staff, while Ramon Rodriguez handled the catching, Cabrera played almost everywhere and Vasquez both held down first base and took a turn on the hill

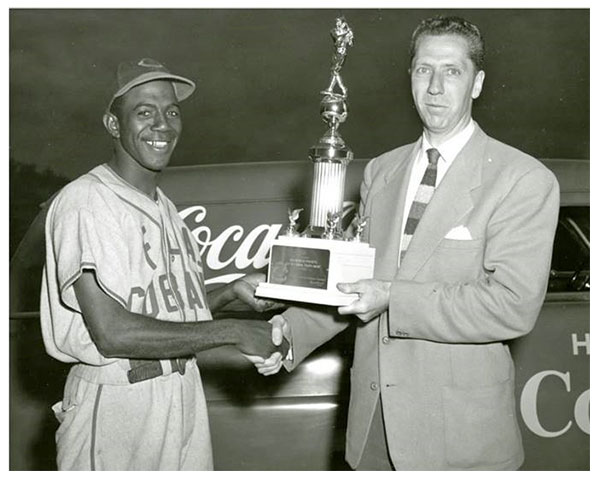

1952 Sask champions!

Playing-manager Gilberto Yzquierdo of the Florida Cubans accepting the Coca-Cola trophy after the Florida Cubans captured the 1952 Saskatchewan National Baseball Congress championship in Moose Jaw by defeating the Indian Head Rockets in two straight games, 9-2 and 16-11.

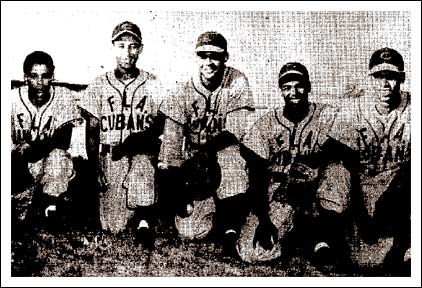

Florida Cubans' infield as the team prepared for the 1952 Lethbridge Rotary Tournament.

Florida Cubans' infield as the team prepared for the 1952 Lethbridge Rotary Tournament.

From left to right : shortstop Ezequiel Diaz, third baseman Leopoldo Reyes, catcher Roberto Ledo, second baseman Julio Bonilla, and first baseman Pedro Seoane. (Lethbridge Herald, August, 1952)

The early teams in Indian Head, Saskatchewan had a core of Cuban players (the Florida Cubans had toured Saskatchewan in 1952, and won the '52 Indian Head Tournament).

The Cubans also captured top money in the 1952 Camrose Tournament. In 1957, Regina worked a deal with Havana (then in the International League) to place five Cubans in the Senators lineup.

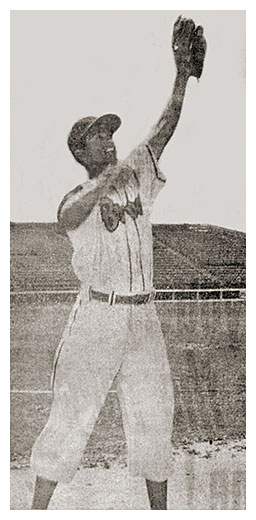

The Florida Cubans captured top prize money at the 1952 Camrose Tournament, downing a team from Leduc, Alberta in the tourney final. Carlos Forten (left) went the distance to get the mound victory. The right-hander took a turn in the outfield when not doing his usual stint on the mound.

Right - Slick fielding shortstop Jose A. "Bobby" Cesar of the 1957 Regina Braves. Cesar drew rave reviews for his work in the field and adept at the plate finishing in the top ten with a .336 mark and leading the league in triples, with 11.

The 19-year-old won a pro contract with the Dodgers and reached the Triple-A level before calling in quits at age 24. Cesar's tenure in the Dodger system coincided with the rise of Maury Wills to shortstop with the major league club a job he'd hold for eight years before being traded to the Pirates. After two seasons with Pittsburgh he returned to Los Angeles for another four summers.

Left - A member of the Florida Cubans accepts congratulations for the Cubans' victory over Baton Rouge Hardwood Sports in the final of the 1952 Indian Head Tournament.

Left - A member of the Florida Cubans accepts congratulations for the Cubans' victory over Baton Rouge Hardwood Sports in the final of the 1952 Indian Head Tournament.

Light-skinned Cubans had been treated much different than Afro-American players by Organized Baseball. Even in the early 1900s, after blacks had been banned from the major and minor leagues, there was a sprinkling of Cuban players, even in the majors.

The Atlanta Constitution of April 2nd, 1916 carried a story listing 16 Cubans in pro ball in the United States, including five in the majors - outfielder Armando Marsans, infielder Angel Aragon, left-handed pitcher Emilio Palmero, first baseman Jose Rodriguez, and catcher Mike Gonzalez. Four of the 16 were playing for Canadian minor league teams - D. Hernandez, utility, Hamilton, Ontario; Jack Calvo, outfielder, Vancouver, BC; Jose Acosta, also Vancouver, who advanced to the major leagues; and right-handed pitcher Mike Almeida with Montreal, Quebec.

In June, 1953, Jim Robinson of Indian Head sent a letter to officials of the Camrose Tournament with news of the Rockets' roster.

"The Indian Head Rockets have been Saskatchewan Provincial Champions for the past two years - 1951 and 1952. They are without a doubt the speediest club on the diamond anywhere in Western Canada, lots of hustle and real crowd pleasers. The majority of the club are Cuban boys, the balance are Americans. The players are practically all young fellows, the playing manger, Gilberto Yzquierdo is 26 years of age and handles the club as a veteran. He himself is an outstanding catcher with a bullet peg and a terrific hitter. We carry a second excellent catcher, Miguel Mirana [sic], who does most of the catching, he is fast, a good hitter and a dandy arm. Six top notch pitchers are carried on the roster - Jose Hernandez, Sammie White, Will Conner, Clyde Johnson, Mario Ruiyol and Roberto Barbon. Four other members deserve special mention. They are Leopoldo Reyes, third base, rated as the best third baseman in the west and property of Pittsburgh Pirates; Juan Prats, centre field; a terrific fielder and lead off hitter, property of Pittsburgh Pirates; Mario Penalver, right fielder, a terrific hitter and excellent fielder; Marcelino Arozarena, utility, a super ball player who plays any position.

In spring training this club lost two games, one being to the Kansas Cith Monarchs, 5 to 3. On their trip from Florida to Canada they were defeated only twice.

Names of the other personnel follow: Pedro Geoane [sic], 1b; Paul Brown, utility; Orlando O'Farrill, ss; Jose Quarino Castilla, lf; Curly Andrews, 2b." (The Camrose Canadian, June 17, 1953)

Mario Amaro Brandon 1952-53 |

Orlando Arango Florida Cubans 1952 Indian Head 1954 |

Cesar Argudin Brandon 1952 |

Marcelino Arozarena Florida Cubans 1952 Indian Head 1953-54 |

Roberto Barbon Florida Cubans 1952 Indian Head 1953 |

Julio Bonilla Florida Cubans 1952 |

Roberto Bouza Regina 1957 |

Rafe Cabrera Brandon 1948-52 Winnipeg 1953 |

Tony Campos Drummondville 1952 Williston 1954 |

Jose Bobby Cesar Regina 1957 |

Ignacio Cisnero Florida Cubans 1952 Saskatoon 1953 |

Ezequiel Diaz Florida Cubans 1952 Saskatoon 53-5 |

Vincente Diaz Lloydminster 1954 |

Juan Dominguez Florida Cubans 1952 |

Sergio Fabre Saskatoon 54-55 |

Carlos Forten Florida Cubans 1952 Winnipeg 1953 |

Luis Fouste Regina 1957 |

Rolando Garcia Indian Head 1952 |

Oswaldo Garcia Lloydminster 1954 |

Jose Guernino Indian Head 1953 |

Jose Hernandez Florida Cubans 1952 Indian Head 1953-54 |

Mario Herrera Florida Cubans 1953 Saskatoon 1953-1956 |

Felipe Jimenez Carman 1954 |

Torribeo Leal Indian Head 1951-1952 |

Roberto Ledo Florida Cubans 1952 |

Miguel Miranda Indian Head 1953-1954 |

Chico O'Farrill Eston 1951 Indian Head 1953 NBattleford 54-55 |

Mario Penalver Florida Cubans 1952 Indian Head 1953-1954 |

Juan Prats Florida Cubans 1952 Indian Head 1953-1954 |

Leopoldo Reyes Florida Cubans 1952 Indian Head 53 Saskatoon 53-54 N Battleford 55 |

Jose Rodriguez Regina 1957 |

Ramon Rodriguez Brandon 1949-1951 |

Pedro Seoane Florida Cubans 1952 Indian Head 1953-1954 |

Armando Suarez Brandon 1951-1952 |

Jose Tartabull Regina 1957 |

Jose Valladares IH-SK 1954 Saskatoon 55-56 |

Armando Vasquez Brandon 1948-1952 |

Gilberto Yzquierdo Florida Cubans 1952 Indian Head 1953-1954 |

Roberto Zayas MJ-SK 1953 LM 1954-57 LM-MJ 1958 |

|

|

Armando Suarez Brandon 1951 |

Pedro Naranjo Brandon 1950-1951 |

In early 2007, Rich Necker, former bat boy for the Florida Cubans during their stint in Saskatchewan, made his first trip to Cuba.

The 2007 Cubana Béisbol Experience From A Canadian Perspective, by Rich Necker

Let me begin by acknowledging my intense infatuation with the sport of baseball, a love that developed as a youngster and blossomed further as I came to fully understand the strategies employed and the many nuances of meaning and expression attached to this game. One has to have maintained the little boy of the past within his being to totally appreciate the romance associated with such affection, a feat not easily maintained in this Canada of ours wherein hockey is king and other athletic pastimes are a distant second. Then, too, there is the cultural shift that now has adults organizing leagues and teams and has taken the fun away from the sandlot gatherings of kids who once played scrub, picked their own teams, did their own umpiring and hardly ever kept score. Fun was the name of the game. Professional baseball players once had to have off-season jobs to support themselves year round but, in today’s society, sport has become a business and outlandish multi-million dollar contracts are the norm and have turned many present and would-be fans away in disgust at the impropriety in the ranking of remuneration.

One will find no such discrepancies present within “el sistema de béisbol Cubano” which is a loose translation meaning today’s “Cuban baseball system”. Prior to the revolution of the 1950’s, the Havana Sugar Kings flourished as a professional Triple A affiliate within the International League. Cuban baseball players were allowed to travel to all parts of the world to ply their trade. As a young lad, I had the immense pleasure of indenturing as a bat boy for a team of semi-pro Cuban players who toured western Canada and consistently finished in the money in the numerous prize money tournaments which were in vogue during that era. I quickly learned, first hand, that Cubans were friendly people and intensely passionate about “pelota”, the name they assign to baseball. After 1959, however, when the revolutionaries came to power in Cuba, a state-run amateur program was instituted, foreigners were not permitted to participate and home grown talent was not allowed to play elsewhere. But, one thing has remained solidly consistent, that being the deep passion that Cuba has for baseball. They proudly proclaim it as their “national sport” and the numerous international amateur and Olympic champions which have come from their leagues attest to their declaration as being the very best or close to the very best. Their teams once piled up an unbelievable 150 straight victories in official international competition over a 10 year time frame (1987-96). Their success at last season’s inaugural World Baseball Classic brought them particular glee in that their amateurs were able to, not only hold their own, but to also beat most of the best professionals from the rest of the world. This is an impoverished country, after all, and the elite baseball players here draw their government salaries, like all other Cuban nationals, from mandatory day jobs for which they earn something in the equivalency of $20-25 Canadian per month. They are consistently inundated with the riches that await them in the professional North American leagues should they decide to jump ship and claim political asylum once within the boundaries of the numerous countries that their All-Star (Olympic) team visits each season while representing Cuba at the prestigious international championship tournaments. There have been a few that have succumbed, the most famous being pitchers Jose Contreras of the Chicago White Sox and Orlando “El Duque” Hernandez currently on the roster of the New York Mets. Almost all Cuban players, however, choose to stay with their national team for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is that they will never be allowed to reside again in Cuba. Family members are generally not allowed to leave the country and join them and are watched closely by government authorities. Yet, there are many who espouse the virtues of the socialist system and remain content with the status quo.

Their 16 team National League began play during the first week in December 2006 and will end in April 2007 with a 3 round set of playoffs. The 90 game schedule that each team plays is based upon the most favorable weather conditions of the Cuban winter months. Cuba is divided into 14 provinces and each province fields one team of their best players. Two teams also play out of the capital (and most populated) city, Havana. One of these Havana based teams, the feared “Los Leones de Industriales”, clad in blue and simply known as the “Industriales”, lay claim to 10 championships including that of last season and are widely acknowledged as being the Cuban League equivalent of the New York Yankees. The 2006-2007 season marks the 46th for this league of Cuba’s elite players. Geography is the sole basis of team designation. Each province’s best players can only play for that team as there are no trades and no free agent signings.

With some preconceived expectations, I eagerly signed up as part of a bus tour that was privileged to attend our very first Cubana béisbol game on Friday evening, January 19, 2007 at “Stadia Generalisimo Calixto Garcia” in Holguin City, the capital of Holguin province. Typical of most ballpark venues in this country, names that are assigned to such are those of revolutionary heroes. I almost had to pinch myself to realize that I was sitting outdoors in a t-shirt and sandals in the middle of January and, not only that, but at night. The parking lot was void of motorized vehicles except for the buses transporting tourists as well as one for each of the teams. Apparently, they dress and shower at a hotel. Local fans in Holguin primarily walked or cycled to the ballpark. There were no commercials on the fences or outfield walls and the only signs that appeared were slogans proclaiming the virtues of the revolution. Admission price was but 1 Cuban convertible peso (approximately $1.25 Canadian), a mere pittance considering the entertainment provided and the skill level of the players. Freshly roasted peanuts, still hot in long cone-shaped paper containers (re-used from newspapers or whatever else was available) sold for 5 centavos (6 cents Canadian). As foreign visitors, we were treated to VIP seats in what they refer to as their PENA section. These were located in the first three rows between home plate and the dugouts and provided an excellent line-of-sight to the action on the diamond. The playing field was elegantly manicured but, despite the VIP designation, the seats were anything but comfortable. Washroom facilities were as decrepit as I have ever witnessed and one tended to hold back for as long as possible without having to make a return visit. Police and military personnel were everywhere but that did not deter the animated Cuban fans from shouting and expressing their feelings toward the opposing team and the disputed umpire calls. Whatever vocal expression these affectionate Cuban fans held back regarding their political and economic system for fear of reprisal, they freely released in other ways within the safety of the ballpark milieu. They rarely were silent like North American fans and fully utilized the freedom of expression allowed citizens at such an outlet. No line-up programs, no scorecards nor team yearbooks are available and it is even difficult to retain your ticket stub as a souvenir since ticket takers tend to keep both halves. In spite of this only being a regularly scheduled league game, the atmosphere was electric and the exuberance of the Cuban fans was really something to witness. One would have thought that this was a sudden death playoff game with all this on-the-edge-of-your-seat enthusiasm and crowd reaction. Clapping cheers, whistle and percussion noise were abound. There are no commercial messages between innings but Cuban music blasts over the speakers while the defensive team takes the field and warms up. At Calixto Garcia Stadium, a roaming band of musicians continually marches around the walkway perimeter separating the lower level seats from those above. While I was wandering this walkway during the game and shooting photos, enthusiastic Cubano fans were standing in the aisles, loudly cheering the great plays made by both teams and inundating me with shots of Cuban rum which I was expected to down chug-a-lug style. By the end of the shooting session, I had to acknowledge the power of both the fans and the rum that had entered my bloodstream (and I am not normally a rum drinker). These fans were not only full of fervor but they really did understand the intricate strategies used by both teams. When all is said and done, the Cubano style of baseball is primarily fundamental, station-to-station baseball wherein sacrifice bunting, well executed squeeze plays, timely base stealing as well as a hit and run style offense have a more prominent role in manufacturing runs than in playing for the extra base hit. The foul poles in this stadium have thin florescent tubes running vertically end-to-end along the actual fair/foul demarcation. At the end of 5 complete innings, a mini-skirted clad lady walks to home plate with a tray of cold beverages for the 4 umpires to consume. The bat boys for both the home team Holguin Sabuesos (Hounds) and the powerhouse Industriales Blues from Havana were old men, probably veteran ballplayers who still have a great love of the game and the clubhouse life. Each time a run scores, all offensive players leave the dugout and high-five the team mate who has just crossed the plate. Following this game, I left the ballpark with a renewed vigor, reminiscent of my youthful enthusiasm . But this was only a prelude of what was to follow.

Unbeknownst to me at the beginning of my trip to Cuba, each provincial team plays a few of their home games in some of the more rural areas, at small antiquated facilities, in order to give fans there an opportunity to see their team play. Think of it in terms of the Saskatchewan Roughriders scheduling a game in Gopher Muscle or Buggywhip. Such a scenario was presented to me on Sunday afternoon, January 21/2007 when the Holguin squad left their spacious stadium in a city of 350,000 to play a home game at rundown “Estadio Mariana Comacho Romero” in the small town of 1500 inhabitants referred to as Rafael Freyre or Santa Lucia. I was able to taxi to this venue but, as I failed to arrive early, all of the 500 or so dilapidated seats were long gone. Not only that but a perimeter lined litany of spectators standing up to 5 deep in most spots surrounded the entire infield and outfield fences bringing the estimated crowd base to around 5000, a monumental feat considering that this sleepy hollow town itself had only a fraction of the total fan count. Only a few 1950’s vehicles (still miraculously in running condition) were present. The multitude of fans had arrived primarily on foot but also via bicycles, tractors, oxen drawn carts, horse drawn buggies, in the back of 3 ton trucks standing up nose-to-nose like cattle packed in for the slaughter house and on horseback or mule. Cattle, pigs, goats, sheep and chickens freely roamed the area. Fans were literally hanging out of trees - I counted 13 in one tree alone - and on the rooftops of the abandoned buildings and shabby schools in the immediate area. People were hanging off of any and every conceivable thing that improved their line of sight. Rum bottles were freely exposed and the contents consumed without any trepidation of police intervention. However, those who over-indulged and created havoc were involuntarily escorted from the stands and driven to the local constabulary in the old Russian built Ladas used by the police force. Fan reaction, however, was no less enthusiastic than within the confines of Calixto Garcia Stadium. Players from both the Industriales and Holguin teams displayed a high level of skill. This excellence of quality of play in the Cuban National League and its importance to both the individual fan and the collective psyche of Cuban society is inescapable.

As eloquent as I have tried to be with my words, the Cuban passion for baseball is really beyond description. One has to see it to believe it ... not only see it but hear it, smell it, taste it and feel it, and you can absolutely use all five senses in experiencing it. It’s a baseball purist’s delight and brings back fond memories of what baseball in western Canada and most of North America was like 55 - 60 years ago. Even when a group of boys congregate on a street corner to play stickball or gather on a dusty sandlot for a pick-up game, it creates “magic in the air” and passers-by will slow down or stop whatever they’re doing to enjoy the spirit of the moment. What I will always remember about this experience is the incredible passion of the fans, the solid fundamentals and the tremendous skill level displayed by these athletes, the infectious schoolboy zeal of the players who freely banter with the fans and outwardly enjoy the simple games of “playing catch” and “pepper” in stark contrast to the spoiled, can’t-be-bothered-with-the-fans arrogance which is constantly on display in Major League ballparks and, most importantly, what I perceived as the fun that these Cuban players appeared to be having in representing their province and country. After all, isn’t baseball supposed to be a fun game? Only in Cuba you say? Pity!

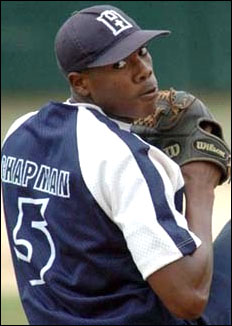

(Left) 18 year old southpaw flamethrower Aroldis Chapman of the 2006-2007 Sabuesos de Holguin baseball club in the Cuban Serie Nacional de Béisbol, the top league on the tiny island.

MY ENLIGHTENMENT & RESURRECTIONBack in Canada following a January 2007 winter vacation to Holguin province in Cuba wherein I was fortunate enough to witness a pair of games in the Serie Nacional de Béisbol and experience the culture of the Cubano fandom, my interest in securing a better quality copy of a tattered team photo of the 1952 Florida Cubans that I had carried in my wallet for over half a century led to my discovery of Jay’s website, already seven years in existence, devoted to the history of baseball in western Canada.

15 years later, our efforts and the subsequent on-line friendship that developed, are about to culminate in the final out in the bottom-of-the-ninth.

Rich Necker

Negro Leagues / Cuban Connection Page-2 Page-3 Page-4 Page-5 Page-6